Holding the Public’s Interest: The Show of Art Conservation

Ruth Osborne

Jackson Pollock Number 1, 1949 (1949). Enamel and metallic paint on canvas. Courtesy: MOCA LA

We reported a few years ago on the well-publicized (and well-sponsored) treatment of large canvases by Jackson Pollock from the MoMA (NYC) and Seattle Art Museum collections. These were Pollock’s One: Number 31, 1950, and his Sea Change (1947), respectively.

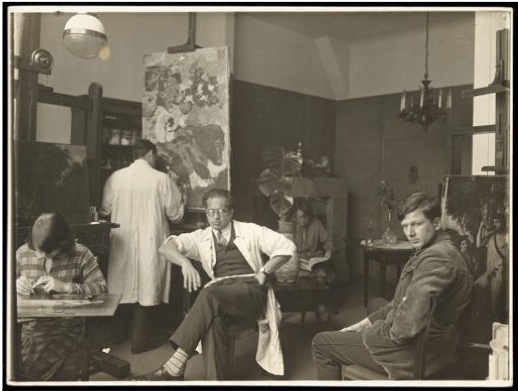

In the case of the SAM restoration, it was asserted this work was in “danger of degeneration” – though no detailed evidence of this was made known to the public nor to reporters. However, keep in mind that when treatment of major works of art for large sums of money are publicly announced or publicly performed, this encourages the science of art conservation to be turned into a sort of strange fishbowl curiosity show. The conservator must work to produce dramatic, noticeably different results on the canvas so as to prove to passersby that their months of work and the funding behind these long-term treatments, is worth it. Sometimes, such treatment is not even considered necessary enough for a collection – yes, even one as large as MoMA – if a corporate sponsor does not step in.

This month, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Los Angeles is to begin a six-month long cleaning treatment of Pollock’s Number 1, 1949 in an open gallery space at their downtown location on Grand Avenue. As per the above expectations of a the now-popular public conservation spectacle, the conservator for this project, imported from the Getty Conservation nstitute, is planned to be on hand during set times to answer questions from public at specific time slots. According to the GCI’s head of science, Tom Learner, the public needs to be shown through this process that art conservation science is fascinating and exciting, producing tangible results and making an impactful discovery:

Conservation is not always the most dramatic thing to watch – we have to figure out how to make it as fascinating as possible.

However, Learner has also said that the condition of this Pollock painting is “good for its size” and is simply being conserved because “it looks a little dull.” Then is an investigative six-month treatment going to truly help the painting itself? Or is it being undertaken half to brighten up a work that’s “a little dull”, and half to make an appeal to the public that the institution has some new entertainment for them?

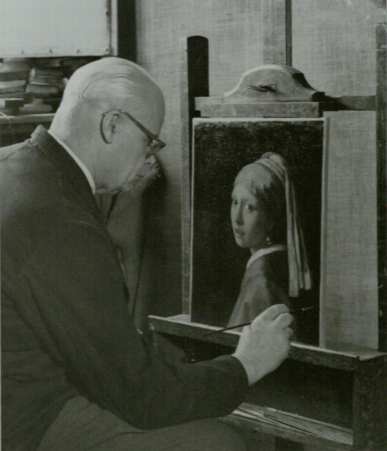

Abbie Vandivere, Girl with a Pearl Earring‘s conservator at the Mauritshuis. Image: Ivo Hoekstra, courtesy of the Mauritshuis, The Hague.

The recently-announced Mauritshuis exhibition of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring is completely conservation-focused and reliant on the work of the conservator as a type of discovery T.V. series called “Girl in the Spotlight”. Daily updates with the conservator leading the team’s testing of each layer of the work are being broadcast as daily “episodes”.

Bank of America doesn’t publicly list amounts given for individual project grants. So we reached out to them for approximate amounts granted each year in total for projects, just to see how these might figure into a museum like the MoMA’s typical budget for conservation. We were told they do not disclose these amounts. Nor do the recipients of the grant monies. But just to give you a sense of how costly major conservation treatments can be, the Getty Conservation Institute’s FY2016 public budget report shows that $1,011,000+ was given to other institutions across just 8 grants. That’s an average of about $126,000 per conservation treatment.

As journalist Tyler Green of “Modern Art Notes” wrote in 2011, art conservation labs on view in museums have turned this work into a spectator sport. Is it to make a greater effort to convince the public of the value of this costly work? Costly, mind you, for both the museum’s budget (or for its corporate or private sponsor), as well as for the surface of the work being poked, daubed, and overpainted. How does this display force the work of art conservation into the face of the museum or gallery visitor in a way that conflates the difference between caring for art and using it to convince ticket-buyers of an art museum’s appeal? Consider this the next time you see announcement of a conservation treatment on display.