What is a Library without its Books? The Battle to Save the UT Austin Fine Arts Library.

By Ruth Osborne

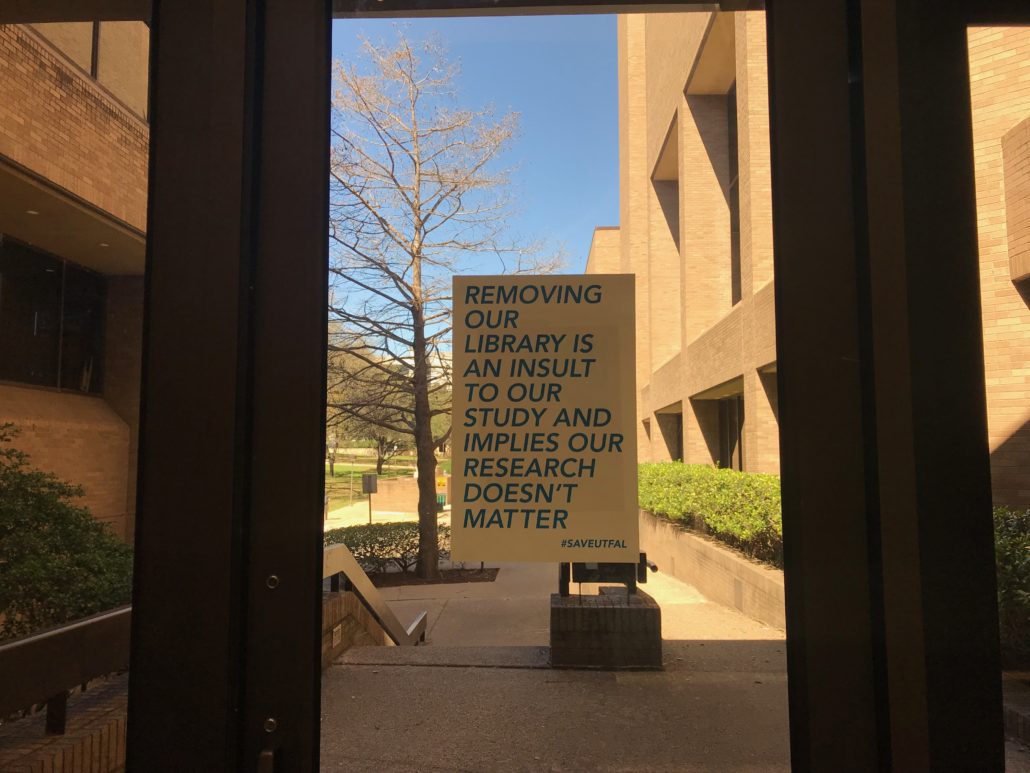

Courtesy: Abigail Sharp.

What happens when a university dean’s initiatives are not in line with those of the faculty and students who actually make up his college? What happens when three departments are pitted against a new one for vital space and resources? What recourse might students and staff have when their educational necessities are devoured mid-course in the interests of a speculative rival program?

At the University of Texas at Austin, a classified Research 1 institution, there recently unfolded a battle between the College of Fine Arts’ three main departments – music, theatre and dance, and art and art history – and the new, untested, and unproven, School of Creative Technologies (just launched this past September).

The College was undergoing increased pressure from its Dean, Douglas Dempster, to further reduce its Fine Arts Library holdings, after having already suffered an drastic reduction since 2016. As related by the “Save UT Libraries” site, the Dean took over two of the five floors of the Library in order to make space for his new vision. The FAL:

suffered the needless removal of 75,000 volumes and the decommissioning of two of its three floors to accommodate a new maker space, The Foundry, an initiative of the School of Design and Creative Technologies” – and to create office and classroom spaces to support the school…because The College of Fine Arts had been unable to raise sufficient funds to finance a new building…The consequent removal of the books and the repurposing of the space was pursued with no consultation of the faculty and students in the College of Fine Arts. Instead, it was presented to them as a fait accompli.

“The Foundry”, now on the 3rd floor of the FAL, offers creative devices like sewing machines, cameras, 3d printers, a recording studio, and video game creation software to students for use on projects. Between 2016 and 2017, over half of the items in the library’s collection – nearly all its journals and a portion of its books – were moved more than 100 miles away from campus to the library facility UT Austin shares with Texas A&M. From the Save UT Libraries’ petition, it is made clear that “books and journals sent to the facility are no longer solely owned by UT Austin and cannot be physically recovered”. We have it from UT Austin sophomore Abigail P. Sharp, whose coursework involves research in art history and museum studies, that these developments have had a rather depressive impact on the building that should be the lifeblood of the College’s campus.

She states that “The Foundry” is “not as often utilized as I would’ve hoped for such an expensive and controversial updating project.” Meanwhile, the new offices and classrooms on the 4th floor are:

very “tech” driven to accommodate space for the growth of the AET major and other Design and Technology related courses and programs. In my experience having one class there, most rooms are often empty. I hope that the re-evaluation of this space leads to some sort of re-implementation of stacks, which would be of more use and value in the DFA Building.

And now, the Dean wants to further expand the new school into what’s remaining of the Fine Arts Library’s main stacks on the fifth floor. Mind you, only 40% of the Library’s collection still remains. Less than half. And it still faces destruction!

While it was announced Friday that the University Provost, Vice Provost, Dean Dempster, and the appointed Fine Arts Library Task Force will now listen to the recommendations of the faculty and students opposed to further erosion of the Library, one cannot be too sure of just what the next steps will be. The Dean admitted, finally, “the centrality of the having these scholarly resources close at hand for teaching and research” as well as “the importance of those resources being available in the heart of COFA [the College of Fine Arts]. Clearly, the current location of the FAL continues to contribute significantly to the sense of community in COFA.” However, there will continue to be a fight over space and resources as the College responds to the Dean’s new School. If the College desires to grow, the students and faculty who have fought against the destruction of their Library and research spaces have demonstrated that they will not let this happen thoughtlessly.

Why should one school in a college overtake the space of another because the college was unable to properly finance a new space for its new initiatives? As it turns out, the College of Fine Arts has historically lacked support from the University since its founding in 1881. According to its website:

The College of Fine Arts was founded in 1937 when an act of the Texas Legislature restored Fine Arts education to the university curriculum 12 years after Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson deleted these programs from the university budget.

The definition of UT Austin under the Carnegie Classifications of Higher Education as a scholarly doctorate-granting university with the “Highest Research Activity (Research 1)” institution is based upon the fact that the University gives the highest priority to research. How can it maintain this exclusive qualification if it cedes thousands of research volumes used by multiple departments to off-site storage?

According to the Dean’s recent statement to the University’s Provost and Executive VP, the intention behind the removal of volumes from the library is to take what is seen as underutilized space and turn it into a new “modern learning and research commons” for use by the larger College of Fine Arts. A Ph.D. candidate at the College of Fine Arts reports to ArtWatch that Dean Dempster “has been met with little resistance outside of the Classics, Art History, and History departments (coincidentally, the people who rely on the library the most).”

The faculty at the College were apparently informed that decisions were moving forward, but in no way were consulted on how to move forward, even though they are the ones who use these resources and depend upon them. First they began relocating series of books, dvds, cds, and music scores from a 4th floor of the library. The 2nd floor currently houses the Dean’s office, faculty offices, sand advising offices. The 3rd floor is now the aforementioned “Foundry”. Finally, the Dean of the College of Fine Arts, the very person put in place to protect these resources and promote them for his college, created two task forces last December to “assess alternative uses for the space on the fifth floor, which currently houses books”. This task force included select faculty, students, and librarians. The results of their findings were reported in a statement this week from the Dean to the University’s Provost and Executive VP. It claims, quite ironically, that though “circulation from the Fine Arts Library collection is steadily declining”, yet “a significant amount of circulation activity continues” and access is “a high priority” for the faculty and students. Who would have guessed.

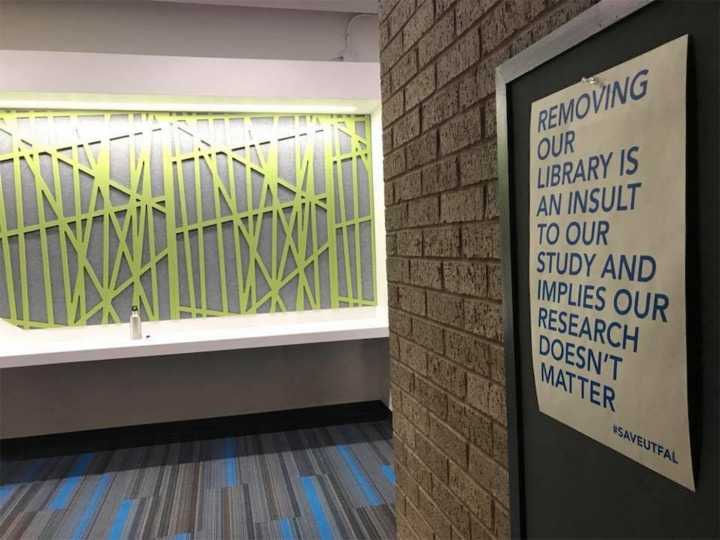

Courtesy: Abigail Sharp.

Last month, the University faculty finally came together to protest the decisions by the Dean. On March 19th, the UT Faculty Council adopted a resolution which protests the removal of materials from the Fine Arts Library. You can find a copy of it here on the Save the UT Libraries site. It states:

The Faculty and Student believe this action will compromise their research abilities and overall education; … being a tier-one research university, the University of Texas will suffer by this action; … Student Government demands more transparency from Dean Dempster and the College of Fine Arts in its proceedings.

What good is a University research library without the very materials for conducting research? How do you boast about having “a community dedicated to the study and advancement of creative disciplines” that is dependent at its very core on engaging with the physical, material world, but also insist that innovation is the removal of the materials of research? It has been pointed out by faculty at UT that this is part of a larger national trend insisting libraries eliminate the space taken up by old stacks and replace it with digitized files. How is this the same? A recent Hyperallergic article by Sarah E. Bond outlines how other public universities across the country making the same snap decisions to drastically reduce or eliminate altogether their library holdings (particularly those relating to the study of history and art).

When it comes to the impact this will have on the research process, as UT Austin student Abigail Sharp relates to ArtWatch:

…the numerous irrelevant, algorithmically selected results from an online database do not compare to the titles found so close to one another when wandering the stacks of the library. Some of the best materials I’ve come across have been analog, and physically holding and flipping through print makes all the difference in learning and retention.

And things like “The Foundry” which replace old stacks in libraries, and which are marketed as innovative “makerspaces”, do not turn out in practice to be the culture changers their promoters hope for them to be.

As for the future of research at the College, Ms. Sharp, Ph.D. candidate in the Dept of Art & Art History Francesca Balboni, and Prof. Rabun Taylor of the College of Liberal Arts provided us with some insights:

What does it now entail to pull a book or journal for research, with several thousands of the volumes off site?

AS: In my recent experience, the library catalog tells you online whether it is in storage or not, and you have to request to have it retrieved, then pick it up at the library. From what I’ve heard from faculty, some take one day, as some have taken up to 18 days. Needless to say, having thousands of materials off-site makes timely and thorough research difficult. It’s one thing to have a source retrieved and end up not needing it when it’s too late to find another, whereas browsing the stacks openly and serendipitously coming across sources and having the ability to determine its value on-site strengthens the research process.

What knowledge is there of the actual digitization process proposed for the volumes removed from the library’s collection?

AS: There seems to be very little knowledge of digitization. Many art history books, music scores, etc. either cannot be digitized or could take a long time. In my opinion, might as well pay to make space for these resources on-site rather than the digitization process. Studies show that knowledge acquisition and retention comes better from analog (which is evidence we have gathered on our website saveutlibraries.com).

If some materials that cannot be digitized, do you know if this is because of their fragility, and they can only be handled by trained special collections librarians?

AS: That would be my guess. I asked some faculty, and what I understand from what was said, reproduction rights are a huge issue – whether from an artist, historian, museum or collector. Therefore, if digitization were to be considered, the cost of purchasing the rights for each material could ultimately add up.

RT: My experience with American and European rights-holding entities (museums, archives, libraries, etc.) is that they often charge more for the rights to publish an image electronically because they presume (rightly or wrongly) that it will get wider coverage in that format. For my last book, I had to ensure that every image I published was cleared for worldwide electronic rights. In many cases, this cost me extra $$$ over and above the fee for print rights. Every entity has a different policy, but many have dual fee schedules for print and electronic rights, tacking on an additional fee for the latter. Now imagine doing that for every image in thousands of print volumes,many of which can’t even be easily identified with a contemporary publisher (because so many publishing houses have changed hands or gone out of business). Current copyright law doesn’t allow a published book into the public domain until 75 years after the death of the author, or (for older books), 95 years after the publication date. In brief, legal mass digitization of a modern print library is completely impossible.

FB: Exhibition catalogues will never become ebooks because it would cost a fortune, especially if we are talking about a living artist with work on the market. But it is another issue entirely if UT begins digitizing books its stored books. I think this “educational fair-use” would require a closed system–only people with University credentials/log-ins could access the material. This is a huge problem for me, given we are talking about a public university… limiting stacks = limiting access. As of now, the UT Libraries have not announced what their plans are for digitizing volumes moved off campus; their focus has been trying to reduce current retrieval-times (from up to a couple weeks down to 1-3 days).

Photo/Courtesy: Abigail Sharp, UT Austin.

According to a page on the UT Austin site devoted to defending the decisions to eliminate stacks and reorient the research process:

Some of the collection could be relocated to other main campus libraries, for example PCL or the Main Building. These facilities are closer to many students’ residences and have more extended hours than the FAL, so relocating the collection could improve access for many.

Are they not here creating the problem they say they’re improving upon? Aren’t they in charge of moving to extend hours at the FAL, as they say they have at these other libraries on campus, and therein eliminate one of the reasons they use to defend their decisions? Another rather manipulative FAQ on this page says:

If I check out more books than I need or drop off books at the reshelving locations, can I influence the circulation count and prevent moving books to other locations?

This is a myth. The strategic needs of the college and the university will drive the future use of library space, including how many print items are stored on the main campus.

But isn’t the real question here “who should decide what the strategic needs of the college and the university are”?

This is a question that will need to be answered as the University and its administration move forward with their promises to listen to the student and faculty recommendations. Take a minute to sign the Change.org petition to help support the continued preservation of the College’s Fine Arts Library:

https://www.change.org/p/douglas-dempster-save-the-university-of-texas-austin-fine-arts-library

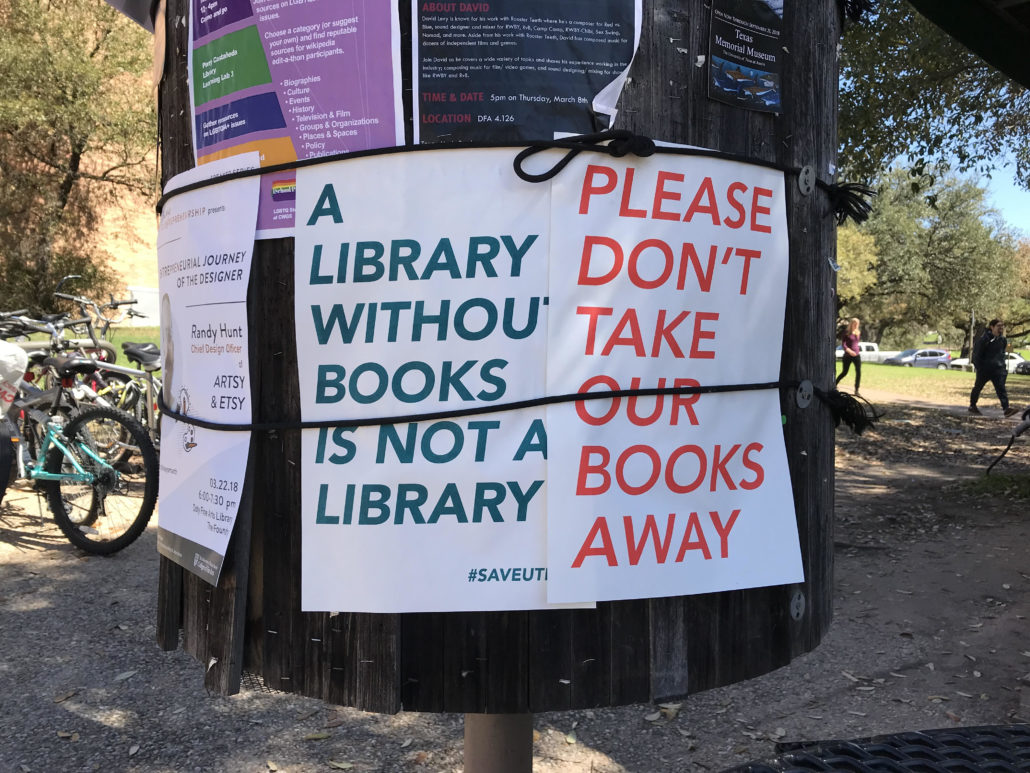

Courtesy: Abigail Sharp.