Mucha’s “Slav Epic” On Tour: What Story Will the Canvases Tell after Two Years of Traveling?

Ruth Osborne

The Slav Epic No. 1: The Slaves in Their Original Homeland (1912). Courtesy: Mucha Foundation.

In one month, an exhibition of turn-of-the-century Czech artist Alphonse Mucha’s Slav Epic (1910-1926) will open to the public at the National Art Center in Tokyo.

The artist’s grandson, John Mucha, has been fighting this action for the past several months. The contracts have been signed, the decision gone to court, and the massive works will now likely be flown from their home at the Veletrzní Palác (leased to Prague’s Czech National Gallery, where the works have been housed since 2010) to go to Japan, then China, then possibly Korea, and afterwards America. These twenty massive canvases (largest measuring nearly 20′ x 26′) could be traveling for up to two years. So why does this still matter to ArtWatch?

Because the decision made by the owners of these artworks will cause irrevocable damage to them without promise of securing a permanent home for them, as was stipulated upon the artist’s gifting the works to the city of Prague with American philanthropist Charles Crane in 1928. When canvases this large are rolled up, transported on airplanes (despite whatever preventative measures of safety are taken), then unrolled again for several shows over the course of two years, the works will no doubt experience alterations in their makeup. The works themselves are composed of both oil and tempera paints applied to canvas, which will react uniquely to the change in temperature and humidity from Eastern Europe to Asia to the North America.

Mucha’s Slav Epic during installation in 2011. Courtesy: The Art Newspaper.

Paintings restorer at the Slovak Academy of Sciences Zuzana Poláková states that “The more Mucha is handled, the less Mucha there is […] Works from Mucha’s Epic have been exhibited abroad several times in the past [during Mucha’s lifetime] and they have always needed restoration. Damage is caused by the repeated rolling and unrolling of the canvases and changes in climate.” Not only are conservators making appeals for the works’ well-being, but so is the Association for the Conservation and Development of Cultural Heritage in the Czech Republic. This nationally-recognized group of conservators has noted one piece of the Epic‘s history that the city of Prague would like to forget: a 1936 investigation by the city council recommending the works not be permitted to travel abroad after having been seriously damaged. While Alphonse himself was still around to restore damages in the 1930s, he is no longer should anything come of this new tour. The works were reportedly hidden during WWII and resurfaced afterwards to be displayed at a chateau in the Moravian town of Moravsky Krumlov in 1963, where they were housed until being wrestled from the town in 2010 and sent to Prague. According to Czech news sources and grandson John’s interview last year with Radio Prague, there are already damages incurred during their installation at the Prague City Gallery.

Mucha’s Slav Epic installed at Veletrzni Palac in Prague. Courtesy: The Naked Tour Guide Prague.

Visualization of the proposed golden donut gallery. Courtesy: Radio Prague/Arpema/Neovisual.cz.

John has further stated that : “[Alphonse] gave it to the city of Prague on condition that it build a pavilion in which it could be exhibited to the public. But the city has not fulfilled that condition.” This issue is a whole other kettle of fish on its own, as the city council’s desire to rehouse the works in a new “golden donut” gallery building without consulting the wider public has been criticized – by one of its district’s own mayors. The works were, in John’s words, “given to Prague, but only as a vehicle, as a gift to the people and the Nation,” NOT to the city Gallery, and “crown jewels don’t usually travel. It was reported by The Economist that, while the city of Prague is arguing they own the works and therefore they have the ability to do with them as they please, that they are also arguing that they cannot be held to account for the artist’s stipulation that the works are provided a permanent exhibition space. Documents from the city’s archives are serving to support the city’s argument that it Crane, not Mucha, who gifted the works. Essentially, they want every benefit that owning this art provides – money from visitors to their gallery, money from exhibit loans – without actually caring for their ongoing preservation if they are to be enjoyed. None of the long-term duties of caring for the works as their original creator thought he had secured. What a surprise! Representatives from the city of Prague (owner of the Prague City Gallery) as well as the National Center for Art in Tokyo have still refused to give comment.

It can be obvious when those in positions of “ownership” of a building or a work of art will have their way, despite the opinions of others in society who care. It can feel pointless to work against one side in favor of having its way because the other side is working against the current of “just the way things are”. But maintaining awareness of wrongs done is not pointless. Opening up dialogue on what is truly the best way to care for art is not ineffective. To say that is to assume that one person’s actions need not be held accountable because they are not impacting another group. To say that is to assume complacency, and take a naïve view that there are no serious wrongs done to things that matter and have an impact on people. To deny dialogue about proper care for works of art is to deny their impact on society.

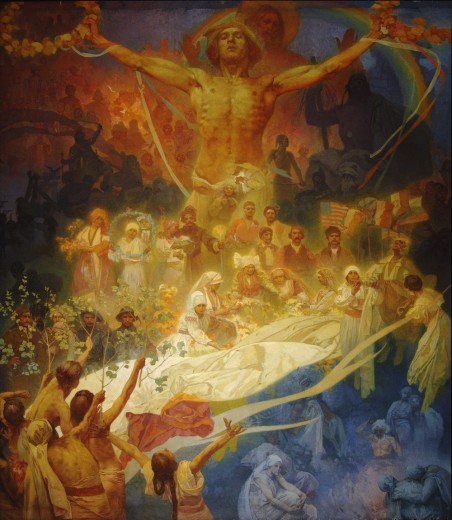

The Slav Epic No. 20: The Apotheosis of the Slavs, Slavs for Humanity (1926). Courtesy: Mucha Foundation.

We’ve covered the case of another massive – and extremely unique – canvas being taken from its long-time home to travel around the world, and then be installed just down the road; in this instance, it was a large Matisse installation from the Barnes Collection being rippled and torn while in transit. For details on Barnes’ Matisse – painted in-situe in the collector’s original home in Merion, PA – before and after it was transported to its new home in Philadelphia, see here, here, and here. More recently, the Seward House Museum in Auburn, NY had decided it would be better to replace its original Thomas Cole – commissioned specially for the house’s owner and given a place of honor in his parlor – with a replica that would supposedly be easier to care for. And, perhaps, so that the operating Foundation could benefit from the sale of the original? While staff at the Seward House have confirmed to ArtWatch that the original has still not returned to the House nor appeared at auction, the staff also remain unaware of what the Board’s intentions might be in the future.

The city of Prague’s ability to rationalize sending Mucha’s Slav Epic on a two year tour also echoes the attitude of the Delaware Art Museum’s Board, when it decided a few years ago to leverage some of its works in order to pay off loans from a recent building expansion. It seems neither the artist nor his/her surviving works have much say in how they are treated less than 100 years after their creation.

If the court decides in favor of the city of Prague, the works will be on display for just two months at the National Art Center in Tokyo (8 March-5 June 2017), before traveling to China, where the works will be shown for just shy of three months at the Nanjing Museum (14 July-8 October), the Guangdong Museum (November-January 2018) and the Hunan Provincial Museum in Changsha (February-May 2018). Venues in South Korea and the US are reportedly being negotiated.

Alphonse Mucha with the Slav Epic in the 1920s. Courtesy: Mucha Trust.