Art Under the Laser – New “Noninvasive” Conservation and Analysis Treatments

Ruth Osborne

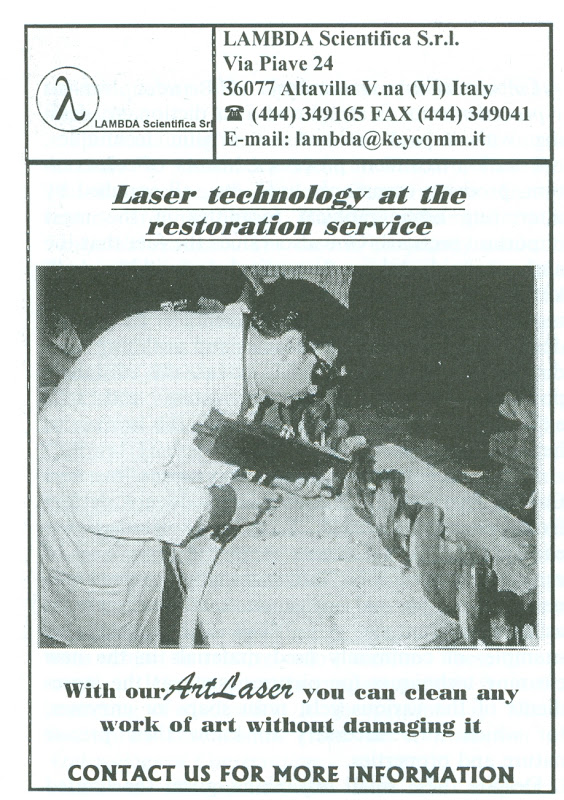

1997 ad that appeared in the professional journal “Studies in Conservation.”

“Shooting a laser at a priceless 14th century painting may seem problematic. But, precisely tuned and timed, the laser system may be the only non-destructive way to get into the mind of long-dead artists…”[1]

This is indeed a troubling statement for the future of art conservation.

ArtWatch has focused attention on the developing relationship between scientific study and the work of art conservators in recent years. The troubling consequences of untested scientific methods applied to renowned works of art has been a concern since before the launch of ArtWatch International in 1992. Founding Professor James Beck and current ArtWatch UK Director Michael Daley have examined such issues in the cases of the 1984 conservation of the Brancacci Chapel frescos and that of the Ilaria del Carretto in 1989.[2] These studies establish the dangerous relationship between scientific developments and their application to irreplaceable cultural works.

Within the past year, molecular biologists at Duke University worked to develop a laser for melanoma diagnoses, and shortly thereafter proposed its benefits to the field of art conservation: “Dr. [Warren S.] Warren assumed that, just as with skin lesions, yellowed varnish and paint layers could be imaged by his laser to distinguish original paint from restoration, helping us understand the intended beauty of centuries-old paintings.”[3] This technique, known as pump-probe laser imaging, creates 3-D cross-sections that show conservators layers of color and material in a work of art, and possibly the materials’ sources in future examinations. Pump-probe laser imaging is described as a way to “uncover the mysteries underneath layers of paint.” This promotes the restoration of paintings as motivated by promised discoveries beneath the surface, rather than for the welfare of the work itself.[4]

Pump-probe laser imaging being used at Duke to analyze The Crucifixion (1330) by Puccio Capanna. Courtesy: William Brown.

John Delaney, a senior imaging scientist in conservation at the National Gallery in D.C., has admitted that the pump-probe laser is not sufficiently tested to be considered ready for serious use in the field: “It’s not ready for prime-time, but it’s showing some real promise, and that’s exciting.” One would hope concerns and doubts already exhibited by specialists in the field would halt or at least slow down work with the laser on paintings. And yet, it was first used on a small fourteenth-century painting by Puccio Capanna, The Crucifixion, part of the Kress Collection at the North Carolina Museum of Art. How and why was the decision made to use this laser on this ca. 1330 painting without sufficient testing, and despite doubts circulating in the field? The hand of the conservator/detective works quickly. Examination revealed a layer of materials that could help authenticate the painting as part of a Vatican altarpiece; and NCMA conservators express a hope they might learn more about the origins and the artist’s intent with future analysis.[5] Similarly appealing discoveries that promised authentication and a new view into the artist’s intent were claimed with the Brancacci Chapel and Sistine Chapel restorations in the 1980s.[6] Will this promote the search for the “true” artist’s hand and authentication of even more works of art with lasers, even if their condition does not necessitate attention from restorers?

Another laser currently being used by North Carolina Museum of Art conservators is the Er:YAG. Dr. Adele de Cruz, adjunct associate professor of chemistry at Duke, invented this tool fifteen years ago for the purpose of removing “old, degraded varnish coatings.” Two videos, produced by Duke University in 2012, show conservators using both lasers to clean and examine the Capanna painting and an ancient Roman marble urn.[7] Newspaper coverage of the pump-probe laser emphasizes its “noninvasive” methods, compared with other techniques of conservation analysis. It is promoted as a tool that can remove what is aesthetically unappealing and leave behind the original work, undamaged.[8] Notions of what might be judged aesthetically unappealing and unoriginal are problematic and potentially question-begging. Meanwhile, such news articles gloss over the dangers posed to the work of art should the conservator’s hand as much as waver. A paper published by Duke University acknowledges the risks that come into play when lasers are utilized in conservation efforts.[9] But while scientists responsible for such inventions may perceive the likelihood of misuse, how much will this really impact the spread of laser treatment throughout the art world?[10]

Doubts still persist in the conservation community as to the consequences of laser work that may be revealed in years to come. These tools require highly skilled hands working with meticulous accuracy and control. They also emit extreme heat levels to the surface of the artwork with each pulse. Changes in a painting’s substrate, binder, or pigment can occur with exposure to such high temperatures. Furthermore, it must be considered that a laser that might have proven effective on the uniform mineral composition of a marble statue will not have the same impact on the softer, more various organic components of an oil painting.

Wolfgang Neustadt, M.A., a German conservator/restorer who works with an Italian laser company and two private international conservators, offers ArtWatch a look into the possible negative effects of laser work. According to Mr. Neustadt, while lasers have proven to be effective in removing centuries of dirt and grime, these tools can also remove parts of original surface material along with that unwanted grime. In some instances, it may be that the laser is not being properly operated and that no supervising body of specialists is overseeing the work being done. Critically, one must consider how the original surface of an artwork changes when cleaning takes place. Unfortunately, what is most often emphasized in reports on conservation treatments is that the cleaned surfaces “look like new,” which, again, begs the question.

Duke University professor Dr. Adele de Cruz and chief NCMA conservator William Brown using the Er-YAG laser in the Museum conservation lab. Courtesy: NCMA / Karen Malinofski, photographer.

In Mr. Neustadt’s experience, those who use modern techniques believe them to be sustainable. New scientific developments, such as those at Duke, are often quick to be slated for use in other restoration projects: “The team is still testing and standardizing the laser system. If the research and development continues…the laser system could be turned into a portable device, making this type of analysis easier for conservation scientists and art conservators around the world.”[11] There is great danger that after laser cleaning tools find favor with highly-skilled conservators, these same lasers will soon after be promoted as low-risk solutions for those with less skill to handle them. Such a development could only increase the risks taken to an artwork undergoing treatment. What would greatly benefit the welfare of our cultural and artistic heritage is some properly accredited and composed authority be established to oversee how, by whom, and in what circumstances conservation tools are handled. How can one tell what the NCMA’s 14th century Capanna painting will look like in 50 or 100 years because of its exposure to the laser now? And how can we ensure that these lasers will be used by the best-trained conservators in future projects? Underlying all practical considerations on the long term effects and consequences of new technical treatments is the question of whether aesthetic, interpretive and historical judgements can ever be devolved to purely technical experts.

At this point it would seem safe to say that not enough time has elapsed to see the changes that might occur and yet, already, these lasers are seen as tools that can help further the abilities of the conservator. In this (optimistic) view, it is thought that art, like science, should improve along with new technologies. William Brown, chief conservator at NCMA, maintains, “paintings once considered impossible to clean by conventional methods can now be returned to their former glory.”[12] While these new laser systems at Duke may ultimately prove more effective than older methods in conserving and examining works, at the same time, we hope those in the arts perceive the possible dangers still posed when handling and treating irreplaceable piece of cultural heritage. With more and more developments in the fields of science and art conservation, who presently is in place to ensure objectively that ethical standards are enforced?

[1] Ashley Yeager, “Lasers ID Ancient Artists’ Intent – A new laser system aids art conservation and restoration,” Duke University Research. Posted 20 August 2012,http://research.duke.edu/

[2] James Beck with Michael Daly. Art Restoration: The Culture, The Business, and the Scandal. (W.W. Norton & Co.: New York and London, 1993) 23-62.

[3] “North Carolina Museum of Art Announces Collaboration with Duke University: Partnership offers art imaging and conservation research opportunities with new laser system,” http://thesnaponline.com/

[4] Martha Waggoner, “Pump-probe lasers expose art mysteries without causing damage,” posted July 4, 2013. Boulder Daily Camera. http://www.dailycamera.com/

[5] Waggoner; “Pump-Probe Laser Imaging to Improve the Arts,” phototonics.com July 2013 Research & Technology. Posted July 16, 2013. http://www.photonics.com/

[6] In the case of the Brancacci Chapel, conservators sought to authenticate specific sections of the frescos as authored by either Masolino or his younger associate Massccio. Meanwhile, the unveiling of a “new Michelangelo” was promoted with the first of the Sistene Chapel cleanings. Beck and Daly, 78-81.

[7] Laser Helps Reveal Details of Ancient Art: http://www.youtube.com/watch?

[8] “Pump-Probe Laser Imaging to Improve the Arts.”

[9] Adele De Cruz, Myron L. Wolbarsht, Susanne A. Hauger, “The Introduction of Lasers as a Tool in Removing Contaminants from Painted Surfaces,”http://monalaserllc.com/

[10] There is already laser conservation underway on delicate frescos at the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii: http://www.quantasystem.com/

http://www.theartnewspaper.

[11] Yeager.

[12] “North Carolina Museum of Art Announces Collaboration with Duke University.”