The Uncertain Future of Local History & Preservation.

Ruth Osborne

Last week, we saw a significant decision that will shape the future of architectural preservation and local history in New York City. And perhaps not for the better.

GVSHP member at the City Planning Commission hearing last week. Courtesy: NY1 / GVSHP.

On Wednesday, the City Council held its final hearing on Mayor de Blasio’s “Zoning for Quality & Affordability” (ZQA) plan, which last week was approved (9-3-1) by the City Planning Commission. As of Wednesday Feb. 10th, the City Council had approved the ZQA, thus allowing more oversized developments throughout the city’s varied historic neighborhoods – neighborhoods that have seen tall buildings go up in recent years without the city requiring any affordable housing units. This is not just an issue in New York – debates over height restrictions and historic district preservation are also occurring over Chicago’s famed Michigan Avenue.

Our colleagues at the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP) have been tirelessly working to demonstrate that the ZQA will in fact not help either quality or affordability, but will surely have detrimental impact on the fifty years of progress made in preservation in the city’s neighborhoods, and in so doing will “[turn] back the clock on years of progress to protect community scale and character.” Their work, as demonstrated by this recent testimony, is not based on conjecture or opinion, but on data from City Council and site-specific studies as well as a thorough understanding of real housing needs. Interestingly enough, GVSHP also reports that: “Many [City] Councilmembers have expressed serious reservations about the plan, but as has been widely reported, the Mayor has been doing quite a bit of horse-trading to try to secure the votes necessary for passage.” What this plan could put into place is the lifting of height restrictions to allow for new development in residential neighborhoods throughout the city. The New York Landmarks Conservancy has also recently spoken out against the Mayor’s ZQA, saying that the City Planning Commission has “[ignored] community concerns” with their vote in favor:

We support the goals of increased affordable housing, but “Zoning for Quality and Affordability” (ZQA) amounts to a “bait and switch.” It doesn’t guarantee affordable housing but it does overturn local planning. It will toss aside agreements that communities have forged with the City over decades. “Mandatory Inclusionary Housing” (MIH) will result in units that remain unaffordable for residents in many part of New York.

What this new development is reflective of, in addition to the renewed proposed landmarks legislation we are sure to hear about in months to come, is that efforts against preserving history and local character are only increasing. This is all happening despite the Landmarks Law having celebrated its 50th anniversary last year – something commemorated at many events in 2015. But commemorating Landmarks Law is not just about patting the city on the back for having done a good job at not tearing down places like Grand Central Terminal, the Empire State Building, etc. It should demand a response to the immediate seen and future unseen needs to continue conscientious development and historic preservation in the city. Or else, wouldn’t we just look like a bunch of hypocrites?

Loopnet Realty ad showing the collapsed section of the Church of the Holy Innocents in Albany. Courtesy: Loopnet Realty.

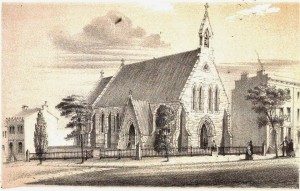

Speaking of preserving local history, the capital city of Albany is in a bit of a mess over one of its historically and artistically significant houses of worship. The Church of the Holy Innocents in Albany, built in 1850 on a major thoroughfare for the local Episcopalian congregation, has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1978. It has also been on the list of Albany’s most endangered buildings for the past ten years. Now, it risks not only rapidly increasing structural damage as a result of its lack of upkeep and maintenance. There is also, as history demonstrates, the potential for the church to be ripped from its historic setting by a larger institution that boasts the finances to preserve it in a new location. This is just one example of the growing trend of local history reluctantly yielding to bigger conglomerate collections or wealthier cities that have the concentrated funds that smaller sites simply don’t have. We saw this with the Corcoran Gallery in 2014 and the Barnes Foundation in 2003.

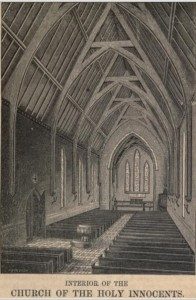

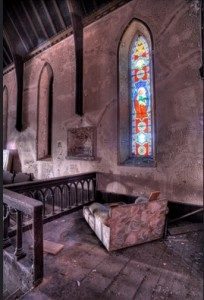

Interior of the Church of the Holy Innocents as it appeared in The Annals of Albany, Vol. X, 1870. Courtesy: Robarts / University of Toronto.

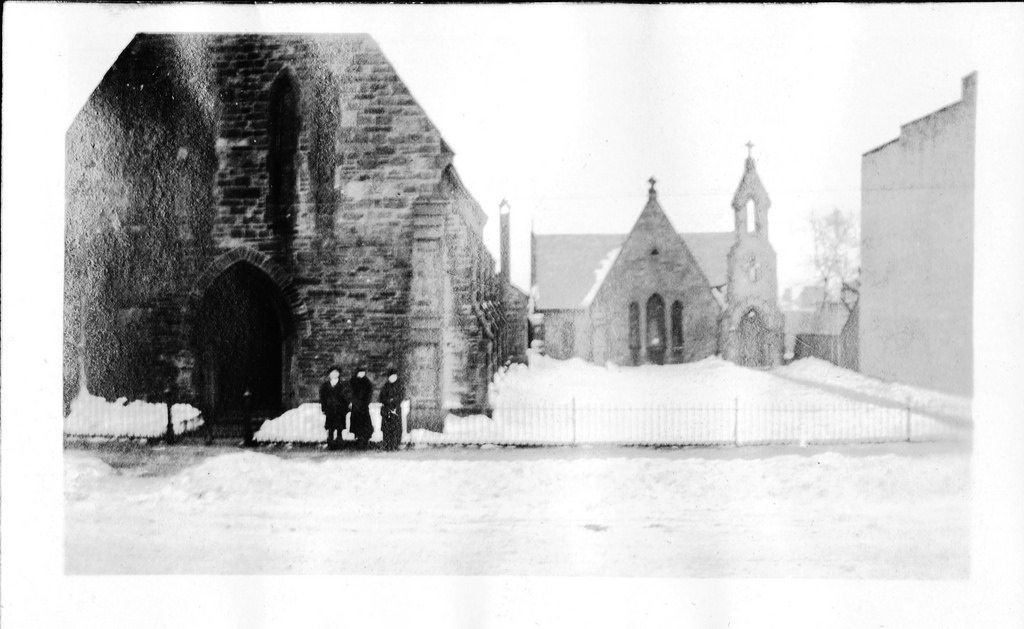

Church of the Holy Innocents in Albany, NY, late 19th century. Courtesy: Paula Lemire / Albany History Blogspot.

As our colleague, Albany historian John Wolcott, provides insight into its historic and artistic significance:

The Episcopal Church was designed in 1850 by architect Frank Willis. In 1866, a chapel was built by lumber baron William DeWitt as a memorial to his children. It was designed by architects William L. Woollett and Edward Ogden. The church (with adjoining chapel) features a small garden and the interior work of John Bolton in its stained glass windows; it is an example of the mid-nineteenth century early Gothic Revival style that so proliferated not only in New York City but throughout upstate New York and gives much of the state’s nineteenth century landscape its enduring character; to attempt to list the number of related structures in upstate New York’s history of Gothic Revival architecture would be overzealous, but suffice it to say that this structure holds much aesthetic and cultural significance for the members of the area.

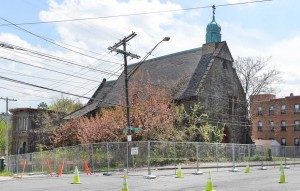

Collapsed part of the Church, captured by local news in Albany last May. Courtesy: WNYT.

The church is currently owned by Hope House Inc., a residential recovery program next door. As Hope House a non-profit organization not designed to care for a historic structure, it isn’t surprising that news report of its collapsed roof and corner arrived last May. Once its immediate stabilization was accomplished, the Historic Albany organization has been monitoring the church’s maintenance. Our colleague in Albany has also written to “Partners for Sacred Places” on the importance of its preservation and maintenance as a historic landmark in Albany, and has been in contact with Historic Albany regarding the urgency of this work:

Church of Holy Innocents as of May 2015. Courtesy: John Carl D’Annibale / Times Union.

This entire matter here has been something of an awful mess for years and became worse than ever of late in spite of constant spin doctoring, but please hang in with it. If you have received a copy of the Realty ad [see above photo]; the main photograph shows a view looking from the nave toward the chancel. Though not too clear here; the chancel arch is completely collapsed. This means that the lettering of a portion of the 23rd Psalm along the lower edge has also been destroyed. One of the most key spiritual artful and historic features of the church. However, in studying recent photos of the debris; it appears that with careful tedious, painstaking sorting the letters could be reassembled to either cement back together but probably to replicate on new stonework that would faithfully replicate that which collapsed.

Interior of the abandoned church, c. 2015. Courtesy: Chuck Miller.

A fear we have currently is whether or not pieces of this beautiful church could be broken down and demolished. It has appeared so far in one realty ad, to be sold for all of $1,000.

A fear we have currently is whether or not pieces of this beautiful church could be broken down and demolished. It has appeared so far in one realty ad, to be sold for all of $1,000. Another option is, unfortunately, to remove the artistic structure and put it back together at another location or museum that boasts the funds to display salvaged architectural remains. Places like The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York have certainly worked wonders in this respect. But if we take a step back from the nineteenth-century cast-iron staircase or bank facade that we’re looking up at in amazement, can we ask ourselves a more serious question?: How can this be beneficial to the stewardship of our local artistic heritage? To tear a historic structure from its original context and setting, which demonstrates its connection to the local community and the cultural and artistic development of an area that has lost many other buildings from this period? To place it in the hands of a museum that would likely have an over-abundance of other significant items from this period? Are we forgetting about the authenticity of place? Authenticity of place is exactly what was lost when Albany saw another of its unique nineteenth-century churches collapse (and subsequently be demolished) due to neglect. Trinity Church (1848) had been designed by renowned architect James Renwick, Jr. – the same who worked on Saint Patrick’s and the Smithsonian Castle.

Trinity Church in Albany, which collapsed in 2011 and was subsequently demolished. Courtesy: (c) Chuck Miller / TimesUnion.

Its stained glass windows, however, were the only pieces salvaged, and which may or may not return to Albany.

Former Met director Philipe de Montebello himself has stated on the importance of authenticity in James Cuno’s Whose Muse?: Art Museums and the Public Trust:

For museums, this should derive from their collections and comprise an absolute commitment to authenticity and to the museum’s authority, which should never be compromised […] It goes without saying that probity should be expected of the museum […] But probity should be found deeper still embedded in our mission, in our thoughts, and in our intellectual approach. For starters and quite simply , since what we promise is authenticity, that is what the public expects to find within our walls. So there must never be any question of a reproduction, a simulacrum, taking the place of a work of art […]

Church of the Holy Innocents, 1918. Courtesy: Coll. Mrs. Weldon J. Vail / Albany Group Archive.

How can we presume to celebrate the authentic and original while at the same time stealing it from its authenticity of place or destroying historic context with disjointed developments? The case for historic preservation presented at Albany’s Church of the Innocents is an example of the fight to retain an important piece of local history in its setting. What makes something historically, artistically, or culturally significant to the point of necessitating its preservation for future generations? Or even to simply retain a visual reminder of a past moment in that region’s history? The character of a historic environment, a historic architectural setting, or a historic neighborhood in New York City is important – it is unique, it tells the story of a community or a people or an artist that makes up a larger culture and society. Those who don’t care to deal with the financial and legal burden of caring for local history and neighborhood character simply attempt to gloss over its importance.

While saving architectural remains from what would otherwise be lost to time is sometimes the only option, ArtWatch would like to ask readers what this means for the future of preserving our local history and cultural heritage? What does this mean for neighborhoods in New York that will in 10 years be unrecognizable after historic structures have been torn down, local merchants removed, and all our architectural history is relegated to sit in fragments against the clean walls of a large gallery? These once were real and thriving buildings and streets, and if we consider ourselves at all connected with their history, there should be conscientious development into the future.

Should all our heritage end up at huge institutions that leave the works disjointed from their original environment? Nevertheless, this what is happening with collections management as well as funding for the arts and history – larger institutions that get the grants and the big donors are financially equipped to subsume smaller collections, which leaves less diversity in museums and less physical presence for local historic collections.