Where One Hand Ends and the Other Begins: Museum Ethics and the Restoration of Ancient Ceramics

Einav Zamir

In February of last year, Kaikodo gallery, a small but well-known commercial venue for Asian art, provided an informational tour of their location to students from the Bard Graduate Center. In what would become a pivotal moment in my development as an art historian, the curator, by way of introduction, held up a small, ancient ceramic cup and proudly announced that its flawless surface was an illusion, and that the object had actually been found “in a million pieces.”

It became immediately obvious that the vessel had been given a thick, unnatural varnish, so as to make it more attractive to collectors. At this point, there was a brief, but discernible shift among my classmates. We remained stone-faced, but glances were exchanged between each of us – it was clear that no one felt comfortable with this restoration.

What I’ve learned since then is that this practice is not at all uncommon, and what’s more, is that it happens in museums and cultural institutions just as often as commercial galleries. In conserving ancient ceramics, viewer appreciation is often considered over viewer education. Of course, these restorations typically begin with the best of intentions. Filling gaps during a reconstruction is, at its core, essential for the long-term structural stability of a piece, as well for protecting the exposed edges of the original fragments from further deterioration, bearing in mind that any added material should always be reversible. However, when a conservator begins to conceal cracks, chips, and break lines for the sake of a smooth finish, a restoration suddenly becomes an aesthetic endeavor, rather than a necessity. Furthermore, by restoring the surface to a pre-break appearance, the conservator is left with two options: to stop there, leaving much of the decorative program fragmented, or to proceed with refilling the missing parts and perpetuate the illusion that the vessel is whole and unchanged from its original state. This is an entirely auxiliary process, as it has absolutely no bearing on the structural integrity or physical decay of the object.

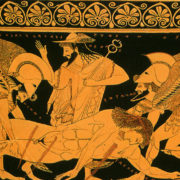

As one might expect, there are various degrees of re-painting. With ancient Greek objects, the more honest, yet still unobtrusive method avoids using black slip to mimic original decoration, so that the viewer has both a means by which to distinguish original from added components, as well a sense of how the original figures or motifs may have appeared in antiquity. This approach tends to be favored by modern restoration efforts, though heavy refilling is still in practice. In both cases, one must consider that the lines which make up the decoration, by the very nature of their execution, are entirely unique and distinct. In other words, no two marks, even on the same vessel, are the same. Therefore, the restorer cannot possibly “re-do” what was done by the craftsman, but rather must extrapolate the character and quality of the decoration, an entirely subjective endeavor. In doing so, the painter’s work is altered and subverted by the hand of the conservator. One cannot know for certain how a form would have extended into a now missing portion of a vessel. Any guesses are not based on ascertainable data.

As one might expect, there are various degrees of re-painting. With ancient Greek objects, the more honest, yet still unobtrusive method avoids using black slip to mimic original decoration, so that the viewer has both a means by which to distinguish original from added components, as well a sense of how the original figures or motifs may have appeared in antiquity. This approach tends to be favored by modern restoration efforts, though heavy refilling is still in practice. In both cases, one must consider that the lines which make up the decoration, by the very nature of their execution, are entirely unique and distinct. In other words, no two marks, even on the same vessel, are the same. Therefore, the restorer cannot possibly “re-do” what was done by the craftsman, but rather must extrapolate the character and quality of the decoration, an entirely subjective endeavor. In doing so, the painter’s work is altered and subverted by the hand of the conservator. One cannot know for certain how a form would have extended into a now missing portion of a vessel. Any guesses are not based on ascertainable data.

What are not immediately apparent in this discussion are the very simple alternatives that exist. An informative label, reconstructive drawing, or digital rendering might accompany an object to fill in the conceptual gaps in a decoration. What’s more, labels should indicate which objects have been heavily restored, and museum websites should point out when repainting has occurred. The British Museum site is better than most in this regard, while the Metropolitan Museum site provides little to nothing in terms of conservation history.

J. Paul Getty Museum associate conservator Jeffrey Maish examining an Attic black-figure kylix under a binocular stereo-microscope. Courtesy: National Science Foundation.

If the restoration or accompanying labels do not make it immediately obvious which areas of the decoration are new, it is not only dishonest, but can also lead to serious errors in interpretation. Fledgling students of art history are often charged with writing interpretive material on vessels as an exercise in formalist analysis. In these assignments, the student is expected to establish opinions based on line-quality, pattern, movement, and form. If a work has been heavily repainted, then the student is likely considering the conservator’s hand equally to that of the ancient craftsman. The exercise is then entirely wasted, and any understanding of the artist’s intent has been lost.

Finally, by not providing this information, museums appear to have little trust in the intelligence and intentions of their patrons. Much like the curator at Kaikodo, who seemed proud of the heavy handed restoration of her ceramic vessel, museums attempt to sell us their collections, rather than create opportunities for honest and unhindered discovery.