How Much is that Rembrandt on the Gallery Wall?

Ruth Osborne

How Much is that Rembrandt on the Gallery Wall?

Do we question the money – and the hands holding the money – behind all the art world’s headline-grabbing exhibitions, restorations, and museum expansions? Furthermore, do we consider exactly how that money is being acquired? It may surprising to some that in the very act of fundraising for such projects that will supposedly help prolong an artwork’s lifetime and educational capabilities, the physical condition of said artwork is actually put at risk! Consider the following…

CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP

Raphael’s Deposition (1507), restored.

Throughout ArtWatch’s 25 years of intervening on behalf of art, we have seen much done hastily with the support of corporate sponsors. Take, for instance, Jaguar’s funding of Raphael’s Deposition in the Borghese Gallery (2005), which removed a not-so-old 1960s-70s varnish only to apply a new coat of “protective varnish” (which will of course yellow as well and have to be removed and replaced in another 50-60 years). Other well-respected restorers heavily questioned the treatment, insisting the work was actually in perfect health already. This is simply one example of restoration being done on a work of art without first establishing a consensus of experts on that artist, who would be able to more thoroughly consider the precise needs of the work in question. Each work of art is a unique living organism unto itself – and it must be treated as such.

It should also be noted that this Raphael restoration work involved the ENEA (Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development). It is an Italian Government-sponsored research and development agency which, according to its mission undertakes research for the purpose of developing and enhancing Italian competitiveness and employment.

In some cases, an emergency repair is indeed required – such as Prada’s recent support for restoration of Vasari’s The Last Supper (which had been destroyed in the Florence flood of 1966). But oftentimes, treatment is taken not with the aim to improve the health or integrity of the artwork. For instance, the Estée Lauder-sponsored treatment of paintings by Tintoretto, Raphael, and San Giovanni at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence between 1999 and 2000.

Tintoretto Exhibition at the Palazzo Pitti.

Funds from Lauder did not prioritize care for works needing minor treatment that might go unseen by the public eye, which would actually be appropriate, as any conservator’s handling of a painting should better reflect the original author’s hand rather than make obvious the conservator’s hand. Rather, the works selected for treatment were those the “erotic intrigues” of Venus that, according to former minister of culture Antonio Paolucci in the small catalogue for the exhibition of these completed restorations, served as a “deliciously effective public relations message.”

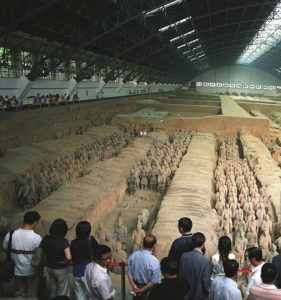

In 2007, Morgan Stanley sponsored a significant traveling loan from China to the British Museum: that of a squad of terracotta warriors from the excavated mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huang. The warriors were included among over 100 fragile, and rather priceless, objects shipped from Xi’an, China to London. This exhibition was intended to draw more attention to on-going excavations at the site, even though the presence of increasing numbers of visitors since the discovery in 1974 has drawn greater concern over environmental damages to the works in situ. Concerns center on the deterioration of pigments on clay sculptures, in addition to other delicate materials such as silks, woods, and bronzes, with the corrosive elements, bacteria, mold, and other foreign pollutants in the environment around the enclosed tomb. The British Museum show, which would also travel to the High Museum in Atlanta, ended up spinning off a second exhibition, “Terra Cotta Warriors”, which brought the ancient sculptures even farther afield – to Santa Ana, CA, Houston, Washington, D.C., and then New York City.

Terracotta Warriors at the British Museum exhibition. Courtesy: Peter Macdiarmid / Getty Images.

Terracotta Warriors at the British Museum exhibition. Courtesy: Peter Macdiarmid / Getty Images.

But the question remains to be asked: why are major companies and donors sponsoring millions in art conservation and loan exhibitions where the money goes in the door and back out again? Millions are being drawn on for temporary treatments that will only last till the next generation of conservators changes their minds, or temporary exhibitions that will only last a few months or years. The Bank of America Art Conservation Project, on which we have posted in here and here, continues to be praised for the great impact and reach it has across many museums in the U.S. Meanwhile, many historic collections are drastically losing general operating support from donors and grant agencies that goes into the long-term care of works of art. Indeed, the breaking up of the Corcoran collection, the National Academy’s move, and the Thomas Cole painting in limbo in the Seward House Museum’s collection all point to the consequences of operating support going out the window.

Credit Suisse at National Gallery 2015. Courtesy: National Gallery.

Other issues come along with major corporate sponsors of restorations or loan exhibitions, including the demand that their marketing campaign cover the historic facade and gallery walls of a museum. Last year’s exhibition of Goya portraits at the National Gallery (London), sponsored by Credit Suisse, also brought prominent marketing opportunities for the Swiss banking group. The banner that ran around the outside of the Gallery in Trafalgar Square featured Credit Suisse nearly as prominently as it did examples of Goya’s portraits for intrigued passersby.

Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, NY. Courtesy: Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

Exhibitions and restoration is not all that is getting funded where operating and research are left in the dust. Major building expansions are also carrot that pulls donors’ hands out of their deep-pockets. Take, for instance, the $100 mil Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Gallery managed to squeeze out for an ambitious expansion.

The press release highlights four major points this huge gift will address:

- “Provide much-needed space to exhibit the collection of masterworks […]

- Create first-rate facilities for presenting special exhibitions

- Enhance the visitor experience with new and better space for education, dining and special gatherings

- Integrate the museum’s campus within Frederick Law Olmsted’s Delaware Park”

As to the specific ways in which the funds will improve curatorial and registrarial care for the works now going out on display, the press release continues with a more ambiguous statement below: “the museum is also seeking to increase its endowment funds to broaden organizational capacity and ensure that an expanded Albright-Knox can thrive in the twenty-first century.”

Sponsors certainly prefer to support the restoration of major mastorworks, rather than ones that might go unseen on the gallery walls. They like to put their name beneath traveling exhibitions that draw millions from around the globe, and in so doing put the artworks at greater risk to exposure or damage. The epidemic of promotional restorations, exhibitions, and expansions is one in which museums market their collection and their cultural relevency like one markets products. How is this trend in sponsorship impacting the care of collections for the future? We would like to pose a few questions as our readers consider other examples of corporate sponsorship today:

- What are the strings attached with corporate sponsorship? How much restoration is now being used as a “come-on” for financial support?

- How is a sponsor’s desire to stick their name brand on the walls of a gallery balanced with the actual work done on the art they are “supporting”?

- How greatly is a company’s sponsorship of art restoration or a traveling exhibition diverting public attention away from some less scrupulous activities they are simultaneously involved in?

CROWDFUNDING RESTORATIONS

Historic collections are also increasingly given to crowdfunding from local residents for conservation projects, creating a sort of conveyor belt-type of system for ongoing work. In many instances, this involves an up-close and personal tour or event in the space or gallery with the collection. But what also occurs at these events are the heavy passed hors d’oeuvres and drinks that get added to the same space with the collection and that can, paradoxically, encourage the objects’ deterioration.

2016 Wishbook. Courtesy: The Patrons of the Arts in The Vatican Museums.

The Vatican Museums’ “Patrons of the Arts” program, which has been going on for over 30 years, sponsors restoration projects throughout its collections that are listed in the annual “Wishbook”. We reported on recent festivities to honor the support of these patrons – a five-day VIP treatment at the Vatican Museums, including “lectures on museum restoration projects, catered dinners in museum galleries, a vespers service in the Sistine Chapel … and even a one-on-one with Pope Francis himself.”

Do we really think we are helping aging works of art live longer by these activities? Issues of the frescoes’ deterioration acknowledged in recent years has brought forth a new call for funding that, instead of working towards a sustainable operating environment and visitor [maintenance] that could slow down deterioration, would enable the millions of annual visitors to view the frescoes enhanced by new LED lighting in the chapel. Instead of seeing a work close to the way it would have been experienced originally as an organic part of the larger structure of the chapel, this new lighting proposes we experience, as Michael Daley has reported “ ‘a completely new diversity of colour’ […] the product of artificially selective sources of lighting, quite unlike anything found in nature and unlike previous systems of artificial light used in churches and chapels.”

Patrons of the Arts of the Vatican Museum.

Italy in particular has become known in recent years for unapologetically reaching out into the pockets of other countries. Major grants have been provided in the past nearly 20 years by the Washington-based organization Friends of Florence. This group of American funders provided $910,000 for the re-opening of the “Botticelli Room” at the Uffizi in Florence in just a few weeks ago on October 18th, where 19 works by the Renaissance master (listed here) were said to be restored before re-installing in two newly lit gallery spaces. As far as we know, there has yet to be published the thorough reasoning behind the restoration of all 19 works at once.

Another organization that provides Italian works of cultural heritage with funding for restoration is the International arm of FAI (Fondo Ambiente Italiano, founded in 1975), organized to promote American and English, as well as broader European, support. Its New York chapter states on the website that it aims at: “safeguarding of that culture through the organisation of events, trips, conferences, seminars, exhibitions and concerts throughout the States.” As American art appreciators and donors are increasingly approached to sponsor restoration, exhibition, and expansion projects at museums both at home and abroad, we would encourage a heightened level of awareness for the long-term impact their support can have on the works themselves.

When the Superintendent of Art in Florence assigned her to treat Michelangelo’s David, an awesome project on every level, those who might have wished that the Gigante be left alone were satisfied that there would be no danger to the integrity of the statue posed by Agnese Parronchi. It would be the crowning jewel of her life’s work, which would give her the kind of world recognition she had earned. When the Florentine officials wanted to impose upon her a very vigorous treatment which included the use of solvents, she did the impossible. She resigned, refusing to carrying out a cleaning which she considered too severe.

When the Superintendent of Art in Florence assigned her to treat Michelangelo’s David, an awesome project on every level, those who might have wished that the Gigante be left alone were satisfied that there would be no danger to the integrity of the statue posed by Agnese Parronchi. It would be the crowning jewel of her life’s work, which would give her the kind of world recognition she had earned. When the Florentine officials wanted to impose upon her a very vigorous treatment which included the use of solvents, she did the impossible. She resigned, refusing to carrying out a cleaning which she considered too severe.

L’esito finale di una iniziativa messa in opera più di una decina di anni fà, quando allora c’era il signor Rollandin, Presidente della Regione, René Faval, Assessore alla Cultura, il Dr. Domenico Prola e Flaminia Montanari alla Soprintendenza delle Belle Arti, si é concrettizzata oggi con questi volumi che contenono gli atti del Convegno.

L’esito finale di una iniziativa messa in opera più di una decina di anni fà, quando allora c’era il signor Rollandin, Presidente della Regione, René Faval, Assessore alla Cultura, il Dr. Domenico Prola e Flaminia Montanari alla Soprintendenza delle Belle Arti, si é concrettizzata oggi con questi volumi che contenono gli atti del Convegno.