Who Gets the Conservation Dollars??

Ruth Osborne

Bank of America: The Art Conservation Project.

The Bank of America Conservation funding program has been lauded for providing large numbers of museums around the world with grant money to restore works in their collections. This program has been going on since 2010 (see here for our earlier background article). While no numbers or even estimates of these funds is given in public documents, nor of the approximate costs of works’ restoration in previous years, it can be assumed that these amounts are staggeringly high.

Take, for instance, some of the masterworks awarded conservation grants in 2013:

Jackson Pollock, Number 1A, 1948 (1948)

Alfred Bierstadt, Sunset Light (1861)

Daniel Maclise, The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife (1854)

Pheonix and Armada portraits of Queen Elizabeth I (c. 1575 and c. 1588)

Rembrandt van Rijn, Scholar in His Study (1635)

Titian, Ecce Homo (1543)

Gustave Courbet, L’Atelier du peintre (1854-55)

Edward Loper Sr., Elfreth’s Alley, 1948. Courtesy: Estate of Edward Loper Sr.

Considering the auction prices for works by these artists range somewhere in the realm of $1 mil+, the conservation price tag for the above pieces are likely tens of thousands of dollars. One would therefore hope that the institutions receiving such large grants, in whom much trust is being placed by Bank of America’s Conservation program, would be ones who’ve proven their trustworthiness to the public that is ostensibly the noble reason behind a conservation project. Then why is the Delaware Art Museum – yes, that museum whose Board slapped the faces of several authorities in arts stewardship just a few years back with its deaccession and sale of important works – receiving money to conserve not one, not two, but thirteen of their paintings?

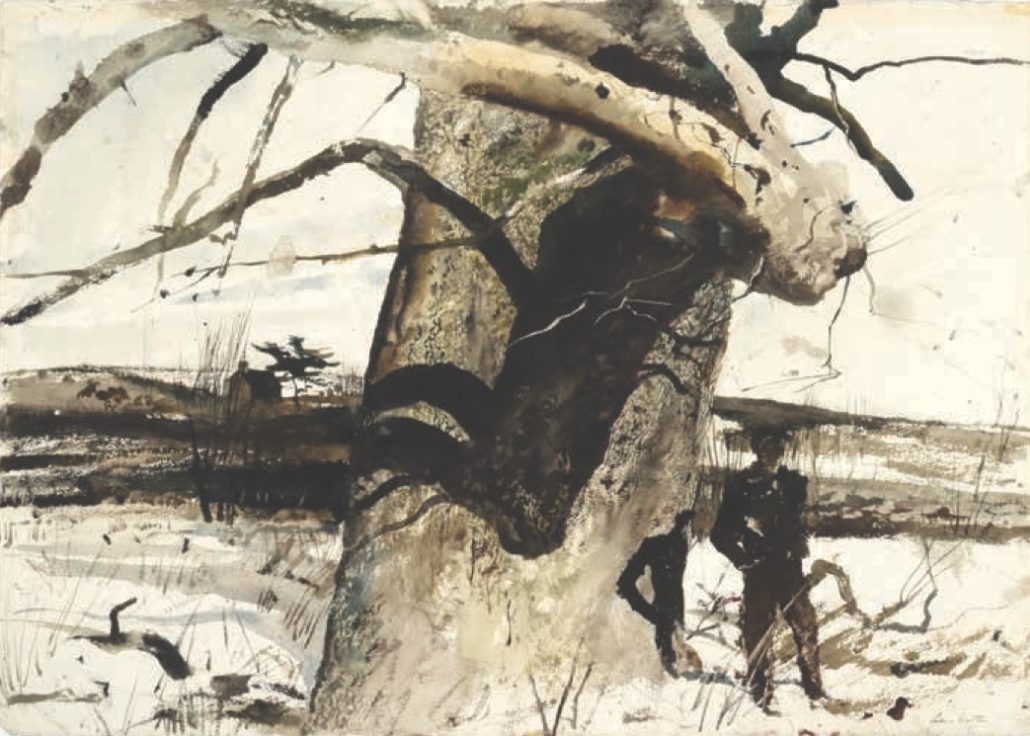

In case you need a refresher, here’s our 2014 post on the DAM’s decision to auction off works by those same artists upon which its reputation has been built over the past 100 years. These included the auctioning of paintings by Andrew Wyeth, Winslow Homer, and Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt. The latter brought in some underwhelming profits, which made the public fear the desperate Museum go even further with more deaccession sales. The DAM blacklisted by the American Alliance of Museums, the Association of Art Museum Directors, and various other highly-regarded arts professionals.

But let’s take a look at how these 13 paintings factor into the overall 2017 list of BoA award recipients:

(1) Art Institute of Chicago – El Greco

(2-4) Saatliche Museen zu Berlin – 3 Renaissance sculptures

(5-10) Brooklyn Museum – 6 Assyrian palace reliefs

(11) Cleveland Museum of Art – Krishna Lifting Mount Govardhan

(12) Courtauld Gallery – Botticelli’s Holy Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalen and John the Baptist

(13) Des Moines Art Center – Heith Haring Dancing Figures

(14-18) Crocker Art Museum – 5 paintings by Wayne Thiebaud

(19-31) Delaware Art Museum – 13 regional paintings

(32) Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco – Morris Louis painting

(33) Isabella Steward Gardner Museum – Farnese Sarcophagus

(34) Hirshorn Museum & Sculpture Garden – 2 works by R Rauschenberg

(35) James A. Michener Art Museum – Henriette Wyeth

(36) Mexican Cultural Institute of Washington, D.C. – 3 fl mural panel

(37) Minneapolis Institute of Art – Frank Stella painting

(38) Musée national Picasso-Paris – Picasso mixed media work

(39) Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid – Joan Miró

(40) North Carolina Museum of Art – Statue of Bacchus

(41) Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan – Giovanni Battista Tiepolo painting

(42-62) The Studio Museum in Harlem – 21 works by Romare Bearden, et. al.

(63-65) Tate Modern – 3 Modigliani paintings

(66) San Diego Museum of Art – Noguchi sculpture

Not only does the DAM make the list with many world-renowned collections of art, but their award makes up nearly 20% of the works to be conserved with this year’s conservation grant! On top of that, the award will go towards at least one work by Andrew Wyeth, whose name was on one of those the Museum sold in lieu of endowment funds a few years ago.

Andrew Wyeth, Pennsylvania Winter, 1947. Courtesy: Andrew Wyeth.