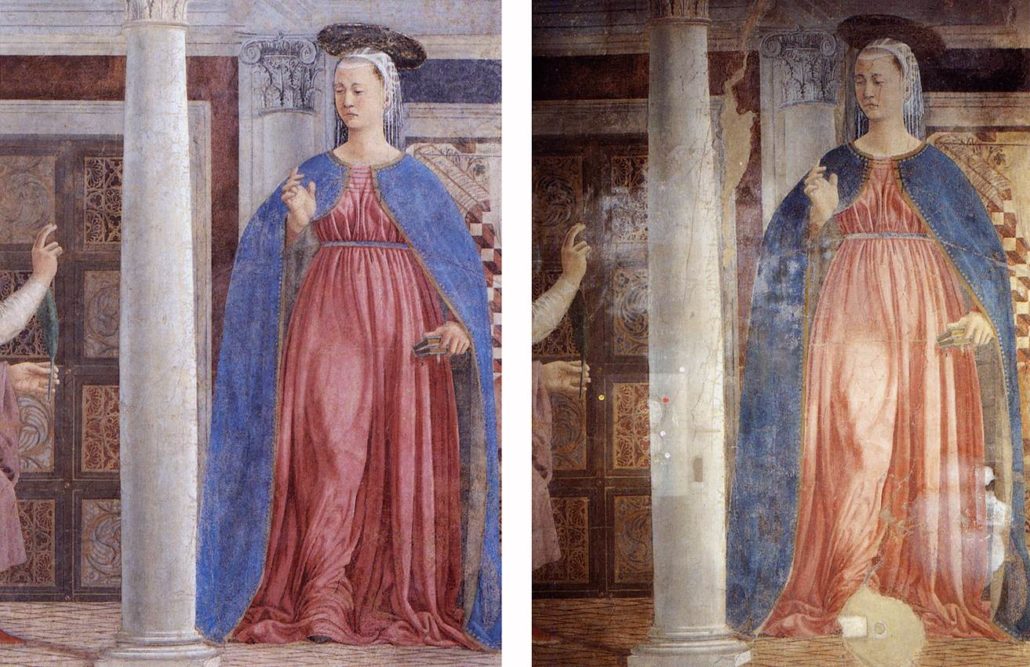

Damage at the Annunziata

Visible evidence of leaks and the need for urgent conservation

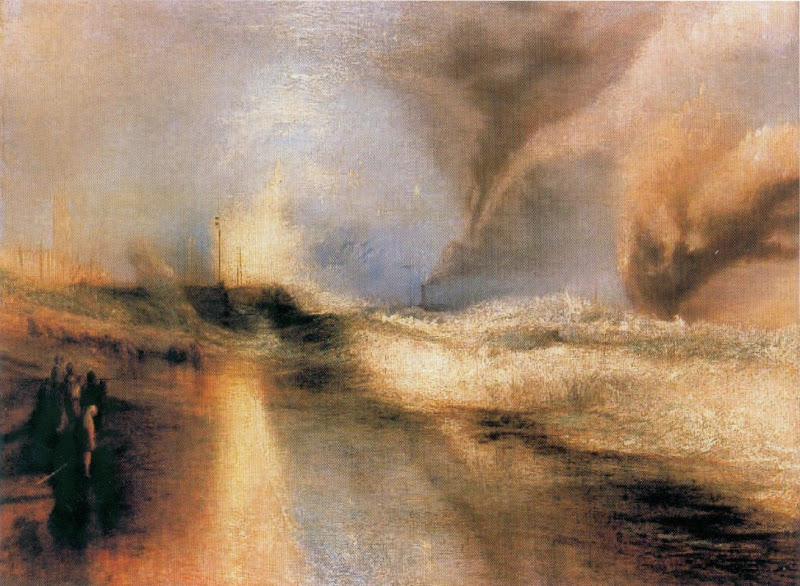

1896 photograph of Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights. Courtesy: Christie’s.

It was certainly the case to my eye that, in those photographs, the plumes of smoke had a very dense and uncharacteristic look to them – resembling tornado funnel clouds and lacking the atmospheric quality evident in the rest of the painting.

While the claim that the handiwork of an earlier restorer or restorers was present was uncontroversial, Mr. Bull’s conclusion that the boat (and its plume of smoke) on the right of the picture had not just been repaired or modified but was probably entirely the product of some restorer’s imagination and therefore “ethically” removable, was anything but. In support of his startling contention, Mr. Bull projected an image of a chromolithograph copy of Rockets and Blue Lights credited to Robert Carrick. This “evidence” was utterly perplexing.

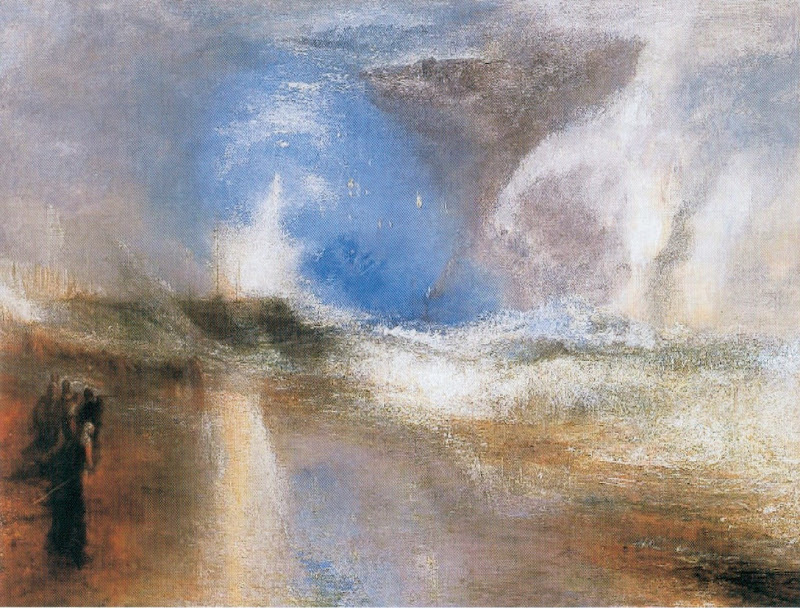

1852 lithographic copy of the painting by Robert Carrick.

As is well known in Turner literature, Carrick’s print of 1852 and a large watercolour copy of it made before 1855 by Whistler no less, both show two boats. A second (c. 1845) now missing painted copy/version of Rockets that has been drawn to our attention by Douglass Graham, director of the Turner Museum, Sarasota, Florida also shows two steamboats.

And yet, in the projected “Carrick” print shown by Mr. Bull, the colours were strikingly light and bright and there was indeed, only a single steamboat and plume of smoke – that being the more distant of the two in the picture’s centre. On the testimony of this singular version of the Carrick copy, Mr. Bull removed all surviving traces of the right-hand boat and its smoke plume along with earlier and crude retouching of them. Further, it seemed clear that in the course of his restoration, Mr. Bull had brought the tones of the painting itself into line with those of the Carrick image he had shown. But from whence had this image sprung – and what precisely was its evidential status?

During the question and answer session I asked if the lithographic print shown was the one produced by the publisher R. Day who acquired the painting in 1850 in order to publish the most accurate print reproduction of it that technology permitted. Mr. Bull and Mr. Rand looked first at each other and then down at a piece of paper on a small table between their chairs. Almost simultaneously they said that they had no idea that Mr. Day had owned the painting. Mr. Rand picked up the piece of paper, saying that it was the provenance of the Rockets and nowhere on it could he or Mr. Bull find any reference to Day’s ownership of the picture. Before I could respond to this surprising claim, another question was taken from another member of the audience. This was disconcerting.

The most widely recognised and comprehensive reference work on Turner is the Yale University Press’s “The Paintings of J. M. W. Turner” by Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll. Although the first edition of 1977 makes no reference to Day’s ownership, the revised second edition of 1984 certainly does. The entry there on Rockets acknowledges that the Turner expert Selby Whittingham had kindly drawn the authors’ attention to Webber’s book on Orrock, a one-time owner of the picture. In it, letters from Day are cited that establish not only his ownership of the picture at the time Carrick was employed to make his copy but that it had been acquired by Day for that very purpose.

Turner’s Rockets and Blue LIghts after William Suhr’s 1960s restoration.

Even if Mr. Bull and Mr. Rand had overlooked the Butlin/Joll 1984 revision, it remains bewildering that they should also seem unaware of the actual appearance of Carrick’s print, as reproduced in the many recent books on Turner and in all of which two steamboats are present. Indeed one such book, the catalogue to the 1998 “Turner and the Scientists” exhibition held at the Tate Gallery, London, was written by James Hamilton – the curator of the Clark’s own exhibition. Did Dr Hamilton express no alarm at the disappearance of one of the two boats about which he had himself commented? It must be thought odd if he had not: the Random House edition of his own 1997 monograph “Turner” has a colour plate of the Clark’s Rockets and Blue Lights, the caption of which states that the photograph was taken before Mr. Bull’s 2003 conservation treatment.

The plate of today’s post-restoration Rockets in the Clark exhibition catalogue shows a strikingly different work. This being so, must we assume that Dr Hamilton believes that some restorer had added a second boat to Turner’s picture between 1851 when Turner died and 1852 when Carrick copied it? If he does, does he have any evidence for it?

In William S. Rodner’s “J. M. W. Turner: Romantic Painter of the Industrial Revolution” (University of California Press, 1997) the author speaks of one ship and her “sister” in text pertaining to the Carrick copy (shown in his figure 33, page 77).

With regard to the evidential value of the Carrick copy, it is important that it be appreciated how unusual and painstaking a production the print was. Day & Son published a collection of plates entitled “The Blue Lights by R. Carrick, after J. M. W. Turner shewing the progress of the printing.” There were no fewer than 27 colour plates. Fourteen plates show each of the single, separate tints that went to make up the image. A further thirteen plates show the successive superimposition of the fourteen tints. Could the image taken as a point of reference by Mr. Bull and the Clark’s curators for their re-working of the painting, I wondered, have been from an earlier, incomplete stage of the printing? (It was, for sure, not the print’s final state.)

A set of the Day & Son’s plates is held by the Yale Center for British Art. Since August 4th I have tried repeatedly to make an appointment (through the Center’s curator for prints and drawings, Mr. Scott Wilcox) to examine the plates. My calls have yet to be returned.

In further justification of his own reworking of the picture, Mr. Bull suggested that the second boat might originally have been added to the picture by the dealer, Lord Duveen in some attempt to pander to the collecting tastes of wealthy Americans. (Twice as much boat for their bucks?) With this suggestion, he was patently and doubly in error. Firstly, Duveen had bought the picture in 1910, some fifty odd years after Carrick recorded two boats in his copy. Secondly, the testimony of the (real, final) Carrick print is corroborated by a black and white photograph of the painting itself published by Christie’s in their catalogue for the June 13th 1896 Sir Julian Goldsmid sale. At that date, the painting and its earlier chromolithographic copy were still quite remarkably in accord. Whatever and whenever damage was done to the Rockets, it must largely have post dated that period and it certainly never included the addition of some allegedly “fictitious” second boat. (Carrick and Day were both alive at the time of the famous Goldsmid sale. Neither is known to have complained about the Rockets’ then condition. At that date, Day, as Dr. Whittingham has reminded us, still greatly regretted having had to part with the picture.)

Image Courtesy: Clark Art Institute.

Ignoring, or ignorant of, all testimony to the second steamboat’s original presence in Turner’s picture, Mr. Bull offered the nowadays Standard Restorers’ Technical Defence in support of extensive removals of paint – namely, that the removed paint had flowed over and into pre-existing cracks in the painting and therefore must post-date Turner’s handiwork by a long interval. When, as here, claimed technical testimony is in such manifest conflict with hard historical testimony, it merits the closest scrutiny and requires some public demonstration and corroboration.

When someone asked Mr. Bull after his talk what had been done to the painting when in the hands of the restorer William Suhr during the 1960s, he quipped that he had no idea, as he was not there at the time looking over the restorer’s shoulder. The jibe cuts both ways: Mr. Bull was there during his own restoration. He claims to have maintained a meticulous daily log of his activities when restoring the picture – and that these logs were submitted on a regular basis to the Clark Institute. Do these records show how Mr. Bull established “technically” that no trace of the right-hand boat – not even the abraded mast and rigging that was still visible in the colour photograph reproduced by Butlin and Joll – was original? Given that Mr. Bull’s technical claims are greatly at variance with the historical record, who might adjudicate here?

When asked what supervision had accompanied his own restoration, Mr. Bull cited the involvement of three individuals associated with the Clark and the nearby Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art – one of the former being the Clark’s own Director, Michael Conforti.

A room at the Clark exhibition was given over to a video presentation in which Mr. Bull and Dr. Hamilton both take pleasure with Mr. Bull’s radical alteration of the picture. I called the Clark Institute to ask the videographer if at any time during the taping Dr. Hamilton had expressed any reservations about the removal of one of the boats. To the contrary, he stated, Dr. Hamilton had expressed nothing but praise for Mr. Bull’s interventions. This raises thorny questions. Was there ever any debate on the propriety of such a radical revision between the restorer, the curators and Turner scholars? If there was, did no Turner scholar caution that the final state of Carrick’s 1852 print and the 1896 Christie’s photograph both clearly show two steamboats? We must assume that none had – how else might Mr. Bull have believed the second boat to be an addition at the hands of Duveen’s restorer?

Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights after Bull’s 2003 restoration.

Postscript

In the absence of any response from the Yale Center For British Art’s Mr Wilcox, I decided to take up these matters with Gillian Forrester, an associate curator of prints and drawings at the Center. Ms. Forrester gave a talk at the Clark Institute’s Turner Lecture Series on August 23rd entitled “‘Enshrined in Mystery, and the Object of Profound Speculation’: The Double Life of J. M. W. Turner”. Ms. Forrester pronounced the Rockets restoration a “resplendent” return of original glory. At questions I asked, apropos of Mr. Bull’s restoration, if any of the Yale Center’s proof sheets of the Carrick lithograph showed only a single boat, and if so, at what point in the succession of superimposed plates the two boats appear together. Ms. Forrester expressed happiness at my question but unhappiness at her own inability to answer it. She had only been made aware of the Carrick proof plate portfolio two days earlier and had not at that point had chance to look at it. Perhaps she had become aware of it in the context of my many unsuccessful requests to examine it. At any event, she did invite me to come to Yale for just that purpose.

I later succeeded in getting a call through to Ms. Forrester in order to arrange the visit. Unfortunately, she said that because of a strike by certain Yale employees, it might not be possible to accommodate me in the near future. Months later, with the strike long since passed, and despite leaving further voicemail messages, I have heard no more from Ms. Forrester.

On October the 8th I put a call through to Mr. Bull at the National Gallery, Washington. Could he say which of the successive thirteen states of the Carrick print he had worked from? He could not. He referred my inquiry to Mr. Rand because he had not, in fact, worked from a Carrick print after all but from a photograph [!] supplied by Mr. Rand of some print about which he (Bull) knew nothing other than that it originated in the Yale Center for British Art.

On October the 9th, I left a voicemail request to Mr. Rand for an opportunity to discuss these matters. To date, he has not responded. Mr. Rand, as mentioned, is the Chief Curator at the Clark Institute. As such, he is answerable to the Director, Mr. Conforti, who in turn is answerable to the Board of Trustees. The reaction of the Clark Trustees to this debacle might well come to be taken as a litmus test of the probity and accountability of the wider system of stewardship that presently governs our public art institutions.

Edmund Rucinski, former Fulbright Scholar, art director of New York City’s department of cultural affairs, and Board Member of the National Society of Mural Painters, is a painter, musician, and an orchestral concertmaster.

The full text of this article is published in ArtWatch UK’s Winter 2003 Newsletter

To contact ArtWatch UK, e-mail artwatch.uk@gmail.com

Notes

¹ Manchester Art Gallery, November 1st, 2003 to January 25th, 2004. For information, call Kim Gowland, Manchester Art Gallery, on 0161 235 8861.

² Margaret F. MacDonald: “James McNeill Whistler, Drawings, Pastels, and Watercolours, A Catalogue Raisonné”. Published for The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by The Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1995.

he Camposanto in Pisa has one of the largest fresco cycles ever painted.

he Camposanto in Pisa has one of the largest fresco cycles ever painted.Produced in the 14th and the 15th centuries, these frescoes were in a vast open courtyard and consequently they did not do well in withstanding the centuries. To make matters worse, in 1944 a bomb struck the building causing further havoc to the frescoes, which were then treated by teams of restorers. The actual paintings, many sections of which were fragmented, were then removed from their original surface and attached to canvas backings.

By no means are these frescoes in uniformly good condition, reflecting for the most part their own historical journey. However, in some cases, as in that of the most famous fresco of the group, the Triumph of Death by Buffalmacco, the works are in reasonably good condition and can be studied and enjoyed. The directorship of the Cathedral had the idea to restore the entire group of frescoes once again, cleaning and replacing them on new canvasses using plastic glue, so that they could be placed back in their original (outdoor) location. During the course of the ongoing campaign, local experts have complained about the harsh cleaning, to the extent that after the intervention there is practically nothing left to be seen.

ArtWatch International seeks a halt to the work until an independent commission can be called, in order to evaluate the work done so far and the feasibility of its continuation. As it now stands the results seem to be a muddle of fragments which essentially has little of the original paint left.

At the risk of appearing obvious, it occurs to me that there are three categories of modern restoration which are effectively operative for paintings and sculptures:

At the risk of appearing obvious, it occurs to me that there are three categories of modern restoration which are effectively operative for paintings and sculptures:In the first, the treatment of works destined for the art market, whether to be sold privately or at public auction, the art trade has certain demands and realities. Once an object finds its way into the hands of dealers, the tendency is to take considerable liberties in order to make it saleable. The dealers seem to know what their clients want, and they tend to give them exactly that. Very frequently, especially in the past, dealers actually did their own restorations, or at least had a restorer in-house who did them according to instructions. In such antiquarian restorations, the governing notion is to make the object as attractive as possible and, to be sure, authentic-looking.

The second category pertains to works in museums and public collections. Whether the institution is public in that it is controlled by a city, state or nation, or it belongs to a foundation, certain controls can be expected, at least in Europe where most nations have Art Ministries and Art Superintendencies with a certain level of jurisdiction. The operative goal in this category is the notion of “legibility.”

Third category, the one that concerns me in this essay, includes works which belong to religious entities and which continue to function as originally conceived, such as wall cycles with strong didactic overtones, or altarpieces with a current ceremonial and theological role.

As a parenthesis, another category can be constructed somewhere between the second and the third, as the church/museum is, in fact, reflective of the newest trend in Italy. Churches like Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, for example, have a dual role, both to fulfil the needs of the faithful and to act as custodian for the Brancacci Chapel, with frescoes by Masaccio, Masolino, and Filippino Lippi. A decade ago, the chapel was transformed into a communal museum at the Carmine with a special entrance, and a prescribed path for viewing the various highlights including a quick visit to the Brancacci Chapel. I suspect those church members especially devoted to Saint Peter will have to do without the Brancacci.

Similar actions have occurred more recently across the Arno at Santa Maria Novella which is more generically a communal church/museum, with an entrance fee and those abominable electronic guides. Accommodations have been made for the faithful, but I suspect they should avoid looking at Masaccio’s recently restored Trinity, or risk the cost of the entrance fee. San Lorenzo in Florence has not one fee, but several: there is one to enter the main body of the church along with Brunelleschi’s unequalled Old Sacristy, another for the New Sacristy (which has long been a museum), and yet another for the Laurentian Library. One should not pick on Florence, however, since many churches in Venice operate under the same principle of the church/museum. In terms of restoration, the question of what is the appropriate mode for such an hybrid institution is particularly perplexing.

I seek here to consider only the third category in connection with an issue which was brought to my attention and which encapsulates a number of vital questions connected with modern art restoration theory and practice, especially in Italy. The object in question is a miraculous, over life-size, painted wood Crucifix which was created for and remains in the Duomo of Crema, a Lombard city not far from Milan. The work, of unknown authorship, probably dates to the 1340s and is neither of exceptional beauty nor is it significant by usual art-historical criteria. Nonetheless, a nexus of challenging issues can be related to it. They include two remarkable, not to say out-of-the-ordinary, characteristics: (1) a historical tradition which connects the Cross with the liberty of the city of Crema, giving it a civic quality; and (2) the tradition of the Cross as the subject of miracles. Especially relevant is the miraculous event which occurred during civic strife in 1448, when an evil man ran into the Duomo, grabbed the Cross and placed it on a fire on the main square. In order to avoid being scorched, the sculpted figure of Christ lifted his feet from the flames, an action which explains the fact that His feet are a few centimetres away from the wood plank to which He is attached.

The sculpture has accrued a black surface over the centuries whose origins are not known. The coloring does coincide with the tradition that it was in a fire, and that may explain this “iconographic” detail. Alternatively, the painted surface might reflect an effort to give the sculpture the look of being of bronze, which turns dark. In any case, the black surface has been a feature of the Cross known and revered by the faithful for centuries. How to deal with it has become the central issue for the current restoration (2000-2001). Should the old, traditional and revered – but not original – black be retained or should it be removed? If the object were housed in the Metropolitan Museum in Art in New York, or the Bargello in Florence, the answer would be much easier to achieve: it would have been removed without much thought. But the Cross is housed in the Duomo.

The situation surrounding the restoration of the Crema Cross has unexpected aspects. The restorer in charge, the Cremese Paolo Mariani has taken a position favoring a minimal intervention, supporting the retention of the black coating. The same view was originally expressed by the Bishop of Crema. The Soprintendente per i beni artistici e storici per le province di Brescia, Cremona e Mantova, with headquarters in Mantova and the authority over Crema, is ideologically on other side.

To complicate this case, the commission to carry out the restoration did not originate from the superintendency, but from the Bishop with the financial support of a local bank. In 1999 the Bishop sought a conservational restoration (“restauro conservativo”) of the Crucifix in conjunction the with Jubilee Year of 2000. Work on this object, most sacred in the hearts of the people of Crema, was handed over to the respected restorer, who is also a professor of restoration. He wanted to make the restoration open to the public at fixed times and was determined to undertake all possible tests to determine the physical condition of the work, including a TAC examination which was actually done at the local hospital. Basically Mariani sought to create a conservational intervention, without altering the traditional appearance of the Cross, thus to maintain what the people were used to seeing. His point of view was consistent with that of the Ufficio Beni Culturali of the Diocesi of Crema.

In contrast, the Soprintendente Dott. Giuliana Algeri intervened with a letter of 19 August 2000, insisting upon the removal of the black surface in order to “recover” the verist aspect of the original. The Soprintendente went on to describe her methodology, which included the “intuition [sic] that beneath there was antique painting which was confirmed by micro-stratagraphic study” (“intuizione che al di sotto ci fosse una dipintura antica che veniva confermata da indagini microstratigrafiche”). Besides she believed that the original painted surface – the one placed immediately on top of the priming layer of gesso and glue – could be found. And further it was expected to liberate further the surfaces in order to recover a chromatic aspect more compatible with the “epochal credibility of the polychromed sculpture” (“veridicta epocale della scultura policroma”). In these remarks we find the authoritarian rhetoric of official modern restoration.

The restorer was clearly in complete disagreement, asserting that “if one were to bring back to their original states all the artistic and architectural works of the past, eliminating all of the events which had occurred in the interim, Italy would be a country in which the works of art would be reduced to embryonic idols” (“se si dovessero riportare allo stato primitivo tutte le opere artistiche ed architettoniche del passato, eliminando tutti gli eventi che si sono materialmente sedimentati nel tempo, l’Ialia diverrebbe un paese nel quale le opere d’arte sarebbero ridotte a larvali feticci”). On a technical level, Mariani claims that what is regarded as original application of flesh tones is in actuality a coat that was applied after the fire of 1448, and not the fourteenth-century surface. But even this – let us call it the second surface – is highly incomplete. The original painting, which can occasionally be seen beneath this one, is present only in a minuscule percentage of the surface.

Notwithstanding his personal opinion, the restorer believed he was obliged, despite his philosophy and his intimate knowledge of the object, to follow the instructions of the Superintendency. He apparently felt that his knowledge and experience was such that it was better to continue to do the restoration rather than to be replaced, presumably by someone with less experience, and therefore salvage the salvageable.

Several conclusions can be reached in this case: (1) the Soprintendente has the final word on the treatment of art in her territory, which generally speaking is an important safeguard against whimsical, parochial interventions; (2) the Soprintendente was neither sympathetic nor aware of the distinctions between the different “kinds” of restorations listed at the beginning of this item and, perhaps unaware, she applied a museum standard; (3) the Soprintendente was much taken with the modern rhetoric of restorations regarding the recovery of ancient splendour, even when very little of it exists; and (4) the restorer, like many of his confreres, is caught in a unenviable situation to either follow the “orders” of the authorities or lose the job; Mariani seems to have chosen the course of inflicting the least possible damage to the work. Should he have refused to follow the instructions of the Soprintendente? My intuition is, probably.

The lesson, if there is one in this case, is that the system does not provide for any significant appeals over the authority of the Soprintendente. Should a system be created in which committees of disinterested individuals can, like a judge, weigh the evidence? Undoubtedly. Such a system would probably have prevented what is unfolding in Crema where the removal of the sacred, traditional aura is perpetrated in favor of a pseudo-ancient one.

One of the least defensible and intellectually questionable concepts raised in the often vitriolic debates surrounding art restoration practice over the past few decades is that of “readability.” A a vague and shifting goal, it continues to be advocated, especially by the museums and state officials around the world. Apparently readability rests at the foundation of French restoration policy. For example, M. Jean-Pierre Mohen conservateur général du patrimoine, directeur du Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France is an unequivocal advocate of readability. (cf. Le Monde des Debats, Septembre, 2000). He states in no uncertain terms: ” La lisibilité devient donc une notion extrêmement important: elle est garante de la part d’authenticité de l’oeuvre, de son état de conservation et de sa capacité a transmettre son message esthetique el culturel.”

If one were to suggest that a Bach Cantata should be transposed and reconstructed to make it “listenable” to a wide audience, many would find the proposition unacceptable. The same might be said of remaking T. S. Elliot’s Wasteland so that the poem would become “understandable” to neophytes and school children. The situation surrounding a painting from the past is rather different in one crucial aspect, however. Re-writing Bach’s musical score for a new redaction or Elliot’s poetic structure for another less complex one does not affect the original text. The correct, uncorrupted text is still there and can always be consulted. Such is not the case with a painting which has been made more readable. The restoration operation requires that making the object more readable be conducted on the original, unique and only text itself.

How does a restorer go about achieving M. Mohen’s much treasured readable image you might quite reasonably ask? Generally speaking any old varnish is removed along with “dirt” from the surface of the painting. In the nature of things, varnish often darkens in time and can turn warm in tone. Of course the removal of such varnishes with solvents can strip the picture of the often admired natural patina achieved over time. Besides, removing one layer on the surface does not guarantee that the layer beneath is not affected.

Restorers almost automatically remove old restorations from a painting. In their place, they tend, in differing degrees, to replace them with modern corrections, under the assumption that we moderns are better at guessing what the correct appearance should be. Usually, too, there is an effort to make the colors themselves more vivid. In consequence the painting becomes increasingly more accessible and attractive to the public. In the process of restoration, especially when readability is the key standard, outlines, edges, contours, which help define the imagery, are reinforced. Even if the original is relatively readable, it can be made more readable. And in areas where the original surface has been lost over the centuries, the restorer repaints them without compunction, in the name of readability. All this happened at the Sistine Chapel where Michelangelo’s ceiling frescoes are today definitely more readable than they were before 1980. To be sure critics and artists have found that the imagery appears to be too much like highly readable Walt Disney illustrations.

Even if the culture could decide what might be acceptable standards of readability, arguably an impossible exercise anyway, will those standards remain the same in 5 years, 10 or 20? Tastes change, as art styles do, and sometimes very fast. One thing is certain in the history of art restoration: experts can quite confidently identify the restoration of one period from another. Thus the time and taste behind the treatment is left indelibly on the unique text.

The concept of readability appears to encompass another characteristic: an aura of democratization. The art object needs to be made assessable to the lowest common denominator. The notion is similar to the one behind Classic Comics, where Dante’s Inferno or the Holy Bible is cartoon-ized for school children. Or consider those nefarious summaries of Moby Dick, The Raven, or Hamlet condensed into several dozen easy-to-understand pages. The process is known today as “dumbing down.”

Readability harbors an hidden agenda: tourism. The tourist industry is one of the leading business of the grandest cities in Europe and America and in places like Paris, New York and Rome, it represents the single greatest income producer for the local economy. In order to make the art palpable to mass tourism, the assumption is that the art objects should be readable, so that the visitors are satisfied in their rushed visits to the Louvre, the Met, the Uffizi. That is interpreted to mean that the paintings must be bright and shinny, and the sculpture scrubbed and sandblasted. In this way, the thinking implies, visitors may wish to return and tell their friends about the marvels they saw.

One cannot forget that restoration is carried out by skillful artisans, steady hands, and the activity being in the final analysis is not science but craft, for want of a better word. Whether in the cleaning stage at the beginning or in the reintegration or repainting stage at the end, the crucial factor is the manual ability and good judgment of the operators. And if the superintendents and museums directors want readability, they can get it only from these individuals, who being human, interpret the pictorial surface, evaluate what clues there are, and make a product which is regarded by the officials as “readable.” This does not even imply that the result is, somehow, correct, original, accurate, or in harmony with the artistic statement of its creator, but merely that it is “readable.” An application of the “readability” approach is the recently completed Last Supper in Milan. Finally, you could say, after centuries of confusion the mural is readable; but the problem is that it is false. As little as 20 percent of what you see is by Leonardo da Vinci and the rest has been painted by the restorers, including the crucial head of Christ which is a highly readable image, datable to circa 1998.

Even bringing the theories of the sacred cow of modern restoration is not necessarily useful nor a legitimate claim to right reason when it comes to modern restorations. The notions of Cesare Brandi, who was neither a scientist nor a restorer but an art historian developed his ideas over 70 years ago. After all if you were to cling to a theory of aviation before the introduction of the jet, or of energy before the atomic revolution, or medicine before antibiotics, the subsequent discussion would prove to be irrelevant to a contemporary situation. When it comes to art restoration there is a far better, safer and more accurate solution to the “readability” requirement, so dear to the official French position. And it is one which preserves the integrity of the original art work at the same time that it employs modern technology.

In order to give the viewer, whether a sophisticated one, a beginner, or a school child, a tangible impression of the art of the past as well as the probable intention of creating artists, I propose that state-of-the-art computer technology be employed to generate to-scale facsimiles and that these be placed side-by-side with the “originals” when they are not very “readable.” This idea surfaced publicly a few years ago when French authorities were considering a thorough cleaning of the Mona Lisa. Complaints had come from museum experts and arts scholars alike over the appearance of the painting, with its darkened, discolored varnish. It was, in effect, difficult to read, and many opined how wonderful it would be to see it freshened up. Good sense prevailed, however, with the recognition that the surface was so delicate and that Leonardo’s process so fragile that losses could have occurred in the restoration. The suggestion was put forward in some quarters to produce a facsimile as one imagines the original appeared. In this way a viable imagine could be offered to the public and for educational purposes, at the same time that tampering with such a basic creation would effectively be avoided.

In fact, the possibility of showing carefully produced scale facsimiles should put an end to the readability alternative with all its built-in threats to the authenticity of the work and the wide margin of error in interpretation. In this way, the text is maintained, never repainted nor brightening up on the basis of one reading or another, even the most qualified. The original remains there and merely requires maintenance. The interpretations, which are inseparable ingredients of restoration, would be limited to the facsimile and could readily be changed from time to time, as our knowledge expands. Under any circumstance it would be more “correct” than any dangerous and essentially experimental treatment of the unique original and would better guarantee the aims of the Restoration Establishment. Let us once and for all eliminate from practice the pernicious and inherently dangerous notion of readability, as outmoded.

It took me too many years to arrive at a fundamental realization regarding the modern restoration industry, its various branches, subdivisions, and operatives.

It took me too many years to arrive at a fundamental realization regarding the modern restoration industry, its various branches, subdivisions, and operatives.

Underlying much of the activity is, of course, money, a factor that I had understood from the very start of my own involvement in the issues fifteen years ago. People need to pay the rent and eat, and it is readily appreciated that everyone down the line — the restorers and their underpaid assistants, their technical backup, their suppliers, the publishers who grind out the expensive new books after every important intervention, the journalists who soak up the news of restorations like a sponge, the art scholars and critics who write the texts, the booksellers and advertisers, the sponsors and their affiliates — has to eat. For better or for worse, this can be apprehended as a fact of life, although not necessarily an admirable one.

An additional element or, better stated, a probable motivation is that of fame, publicity, being invited to the right parties, being on the cutting edge, being envied, being hailed in the mass media as uncoverer, being sought after as a person deeply involved in the rediscovery of Leonardo’s original miracle, of Piero della Francesca’s real color, of Hans Holbein’s true intentions. By an alchemical transference, those involved in highly visible restorations (alas, no one cares about unimportant or minor ones) seem to accrue some of the creating artist’s force and genius. Who does not desire to appropriate even a fragment of Michelangelo’s power, Masaccio’s monumentality, Rembrandt’s insights, or Cézanne’s structuring? I have reluctantly and sadly understood that all of this is a fact of life, too. The Preacher of long ago knew very well the dangers of Vanitas.

For some time, I have also recognized that great museums of the world are deeply conscious of their reputation, together with the realization that the restoration of their objects goes a long way in defining them. Everyone (except, seemingly, the individuals directly involved) recognizes that London’s National Gallery has had — and continues to have — a dreadful record, perhaps close to the top of the list of world-class institutions that have systematically ruined masterpieces under their guardianship. The Prado, which has justifiably come under severe attack by a Spanish weekly, El Tiempo, is earning for itself a similar reputation. Washington’s National Gallery is hardly better as it advocates the English method of scraping everything off and then doing it over. And God forbid if there is “yellowed varnish” — worse, even, than yellow teeth. Nor is the Metropolitan Museum in New York immune to similar characterization. To be sure, its old-master collections have been systematically over-cleaned for generations, as its director once admitted to me, so there is not much left to argue about. The Louvre’s record is spotty, with some restrained interventions while others have been zealous. Raphael’s Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione has become a dingy but heavily varnished gray and now looks more like a Manet than it should. And so it goes. Although the pride of the museums can be understood, with long and often distinguished traditions, their actions must be evaluated critically and not praised indiscriminately merely because we “love” the Louvre, the Met, and other grand institutions. On the other hand, I can say that the State Museums in Berlin, Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, and the Hermitage have avoided the worst scenario and have every reason to brag about having practiced healthy restraint. One can only hope that the temptations of vast sums of American foundation money will not induce them to drop their time-honored methodology.

The element I had fundamentally failed to evaluate properly until now is that even governments believe that they have a vested interest in conservation and restoration activities conducted within their borders or carried out by their citizens. A misplaced jingoism prevents dispassionate and disinterested international debate. And, worse still, it silences those within a country who, if they are inclined to speak critically about a particular restoration, become fearful of injurious repercussions or fail to enunciate their reservations out of misplaced solidarity or assumed patriotism. In Italy, the government has effectively blocked criticism of the endless, questionable Last Supper cleaning and repainting. To have spoken out meant surely being blacklisted from various perks that the minister of culture and the mechanism in general can provide, and very few have taken the risk.

One of the standard techniques used to stifle criticism is the demand on the part of the restoration process that individuals inclined to express reservations must have closely inspected the cleaned and restored work before being considered credible. The Sistine Chapel restorers and their public-relations consultants were particularly skilled in refining this requirement. For example, if one actually saw the restored ceiling in person and still harbored suspicions, the question was raised about how much time was actually spent on the scaffolding. If it happened to have been a brief visit and an individual continued to be unconvinced, he would be belittled since he had been there only an hour or two. If resistance persisted, another ploy was used. The question was raised about how many times the unconverted individual actually saw the restoration in progress: if only a few, the naysayer was described as unserious or poorly prepared to comment.

And if one miraculously passed all these prerequisites and stood firm, the demands were expanded. For the really stiff-necked, the requirement became: one really should have followed the work step by step, day by day to understand fully what had been done. Of course, the only people left after all these conditions were met were the restorers themselves and a handful of supervisors connected with the cleaning and repainting. This systematic elimination of criticism turned out to be a brilliant tactic for stifling serious debate. And even if all the tests were passed with flying colors, one failed anyway, for “it is as difficult to judge a restoration as it is to judge a surgical operation” (E’ difficile come giudicare un intervento chirurgico], according to Dr. Giuseppe Basile, a top official of the Istituto Centrale di Restauro, in a talk presented to the Accademia dei Lincei. In other words, there can be no criticism; leave it to the operatives; do not rock the boat.

Argumentation along these lines has been so powerful that persons who might have an opinion about one or another restoration refrain from expressing themselves publicly on the subject. They have, in effect, been brainwashed into thinking that, after all, they cannot utter a word until having seen firsthand the finished product. Sometimes they never to because not doing so is an excellent way to avoid taking a stand on a controversial cultural issue, and I know of art historians who make it a point never to see recently restored works (and who can blame them?). Not having seen them, these scholars are effectively off the hook. I have sought for years, with no success, for a competent sculpture expert to comment on the restoration of the fragments from Jacopo della Quercia’s Fonte Gaia in Siena, which are systematically being cleaned. Either these experts have not seen the pieces or they pretend they have not seen them.

After moving around the edges, I am now prepared to deal with the issue straight on, seeking to impose a little logic on the “Have you seen it?” qualification imposed by restoration proponents. The requirement of up-close viewing is nonsense. In the first place, the presentations are often manipulated by theatrical lighting and, under any circumstances, not the lighting that the artist envisioned for his painting. Then one must suffer through the restoration rhetoric of official explanations. The purpose is to find out whether the person “likes” the result or not. Of course, liking or not liking the appearance of a recent restoration has nothing to do with its accuracy, historical correctness, the losses and gains, the changes, not to mention the quality of the intervention. Many people “like” the new Sistine Chapel frescoes as they might like a B movie or a popular musical comedy, but what does that signify about the quality of the cleaning? Liking or not liking the new appearance does not deal with the issue of authenticity or the need for restoration and has little to do with a critical evaluation of the intervention. On going to the refectory to see the restored Last Supper, one finds an isolated artifact out of contact with its history. The previous state (or states) is (are) gone forever so that serious comparisons are impossible.

The truth is — as serious scholars have recognized for decades — that, as in advertisements for weight-loss programs, seeing is believing. Only the combination of a “before” and “after” view can produce a sensible conclusion about a restoration; even expert memory has limitations. Who can now “revive” in his mind’s eye Masaccio’s Brancacci frescoes after fifteen years and with all the verbiage that has poured forth in the interim? Careful confrontations are necessary; ones that respect scale are a requirement. In other words, holding a book of color reproductions of the pre restored object and comparing it with the original on an entirely different scale is not illuminating. A more critical study can be carried out with quality photographs, which art scholars have used to advantage as aids for more than a century. Ideally, the photos should be in black and white, for variations in color merely add a further complication to a proper confrontation. But even a one-to-one comparison is not sufficient for a balanced evaluation in this day and age. Before repainting is begun, one needs vital “during” photographs as well in order to determine what has been taken off. Further evidence can also help, including raking light, infrared reflectography, ultraviolet and X rays, which can often provide evidence upon which to base a reasoned judgment. Merely to go before The Last Supper as it now appears and to utter an impressionistic evaluation is beside the point. The requirement should be not “Have you seen it?” but “Have you studied the evidence in a dispassionate, independent way, using the whole range of unavailable evidence, including ‘before,’ ‘during,’ and ‘after’ photographs?”

Seeing the restored original has a built-in disadvantage for evenhanded critical evaluation. The aura of a Leonardo or a Correggio, however much it has been belittled by restorers past and present, retains enough of the creating artist’s ingenuity to overwhelm. The restoration establishment and their sponsors collect the benefit of whatever is left of the original to help them carry the day, even if a great deal of the original has been lost or a great deal of new painting has been added. The same is true for the Sistine Ceiling, for whatever the losses (and in my view they are considerable): all the secco, the added layers or veils, the pentimenti. But behind it all is Michelangelo, and even a fragmented, crippled Michelangelo has residual power.

After all, the number and the extent of restorative interventions has exploded within the walls of world-class museums, illustrious churches and public buildings. No discrimination is discernible in terms of objects’ origins: ancient, modern and everything in-between is proper fodder for the ever expanding, voracious restoration mechanism. Symptomatically, international fairs devoted to restoration are flourishing in many countries, including in the United States and Italy. Universities too have gotten into the act while restoration schools and how-to institutes have cropped up everywhere. Even part-time training is available so that after a matter of months at a nondescript night school, an individual can hang out his or her shingle as a proper restorer. After all, in most countries, no state examinations nor certifying structures are in place for this profession. I recognize, of course, that serious training institutions may be found in many places although even in them, no consensus has been reached about the curriculum for producing graduates. And of course, I realize too that honorable and moral practitioners of the activity abound. However, the overall training component of restoration has grown enormously while the entire enterprise remains totally without oversight. Even the distinction between restoration and conservation has not yet been clarified. Despite such deficiencies, the broader society seems prepared to accept whatever is fed to it regarding restoration issues.

The issues surrounding modern restoration are by no means limited to the heralded pictorial interventions like the Sistine Chapel frescoes or Leonardo’s Last Supper. Much of the ancient, medieval, Renaissance, Baroque and Neo-Classical sculpture, in all materials, has been systematically ‘adjusted’ to meet certain undefined standards but with all-too identifiable effects. Architectural restoration, doubtless a more profitable activity than restoration of painting or sculpture, can be seen at its best (or really at its worst) in today’s Rome where preparations for the Jubilee provide a frightful testimony as to the prevalence of this type of restoration effort.

It may not be an exaggeration to declare that the past in England, France, Germany and Italy, as it has been preserved in its art and architecture, is becoming unrecognizable. All this is not to say that previous epochs have not done their share of damage to beloved buildings and respected art treasures. But we today, being practically into the twenty-first century, think we know better than our predecessors, and are certainly cognizant and often critical of the losses that have occurred in the past. Yet individuals are few and far between who are prepared to plunge into the troubled waters of restoration discourse and question the current situation.

Even art and architectural historians whose very subject matter, whose raw material, whose database, so to speak, is experiencing daily transformation before their eyes have been reticent about engaging in the issue. When they do, they are more often than not unwilling to enter into anything like open debate. This inexcusable avoidance requires explanation and comment, if for no other reason, than to set the record straight. One element of this reluctance must be self-interest. To swim against the high tide of art cleaning, which became a dominant museum activity over the past two decades, results in becoming ostracized from the museum world and its perks. Those blockbuster shows like, the Vermeer, the Lotto, the Matisse or any other, are intimately tied to restoration because of the ugly habit of preparing the works to be exhibited so that they appear in a “refreshed” mode which usually means that they are homogenized with all the others.

The ‘new’ interpretations of one artist or another which results from the blockbuster offers the art historian the opportunity to participate in the resulting symposia and international congresses. The same is true following the restorations of well-known or important works. These too require a whole new apparatus. What art specialist would be willing to forego a role in these activities? This would mean being left out of the massive catalogues that usually accompany art spectaculars. For those who enjoy it, there are also opportunities to participate in television interviews, or appear on any accompanying CD-ROM merchandise. Each of these can involve substantial compensation. To be at odds with the museum community means to forego all of it.

Who is so naive as not to realize that anyone who appears too negative toward the “new” (or to use one of the more popular operative words, “glorious”) appearance of recently cleaned art works is rarely the favorite candidate to write monographs, catalogue introductions or items in prestigious journals? Such opponents are, instead, marginalized. Even their grant-winning capacity can be jeopardized by what is regarded as a hostile position towards modern restorations. This bias is quite similar to the one shown to those who are unsympathetic to the dominant contemporary art styles. Of course there are those specialists who in good conscience regard the interventions as necessary, healthy and even excellent, and believe that they demonstrate scientific progress in restoration activity. My own bias is that these individuals are unable to really “see” works of art. Nevertheless, what is truly confounding about their position is that they are extremely reluctant to engage in serious discussion of the matter. That failure, in my view, basically disqualifies them from being taken seriously on the issue.

Often, it is this same category of individuals who in taking pride and having confidence in their skills and especially in their “eye,” rely solely upon these abilities as proof of the validity of a restoration. Of course, like art itself, the ability or the absence of ability to confront art objects, is always difficult, if not impossible, to quantify. One’s position in the art world is usually taken as proof of such an ability. But a university post, directorship of an institute, a government or museum position should be regarded as license to avoid serious debate on the issues surrounding modern restoration. Regularly, however, they are.

If specialists’ reluctance can be explained as I have suggested, or at least if my proposals can be taken as highly plausible, one is left to speculate as to the reasons preventing the larger intellectual community from taking part in this issue (the matter cannot properly be referred to as a debate because exchanges have been only sporadic and isolated). I am inclined to explain this negligence on the basis of the visual insecurity that pervades our entire culture, even among the elite, especially since the domination of abstract art. If one has serious reservations about, for instance, arte povere or Neo-Dadaism, following such art’s fifty plus year hegemony, it is difficult to say so publicly without sounding like a totally uncultivated and uncivilized reactionary. Thus, the time in which a writer could seriously deal with art seems to have passed. This is most true of discussions of contemporary art but also holds in discussions of older art as well. When combined with the bias of an age that admires (only?) the opinion of the specialist anyway, the temptation is strong for scholars outside the immediate field to remain silent. Who wants to be belittled as being inexpert, poorly prepared or even foolish?

However, such an eventuality is very real, given the overlay of science on modern restoration. When the operatives in the restoration field call upon “science,” humanists tend to tremble and shy away. Of course it is never mentioned that a determining role of science in the process is very questionable in the first place. It is applicable mainly for purposes of diagnosis; as a data supplier. The notion of a scientific repainting is a nonsense. Additionally, what humanists often tend to forget is that scientists differ among themselves all the time so that science in art restoration rarely, if ever, offers a single answer.

Still more to the point in explaining the reluctance of the intellectual community to critically examine questions of modern restoration is a widely diffused crisis in perception which, I fear, also encompasses the very restorers who are at work daily on our treasures, not to mention their supervisors, those high-minded and high powered museum directors, curators and superintendents. After a generation of almost constant bombardment of plastic colors, of back-lit television tubes, of videos, computer screens, signage, magazine illustrations, and more recently those rather dismally colored daily newspapers, our communal vision cannot fail to have been affected. Coupled with a crippled color sensibility, is a diminished orientation toward comprehending sculptural volume. From the Renaissance onward, at least in painting, credit has always been given to those artists who could make the objects they depicted seem as “real” as they appeared in nature. With the art of the past century, since artistic goals began to be replaced by others in which the flatness of the picture plane gained prestige. The perception of earlier art, as it was intended to be perceived, became more difficult. This factor must have compounded the more general visual insecurity mentioned already and, if taken in conjunction with the opinions of restoration-at-any cost proponents, inevitably results in a certain confusion.

–Reversibility–

Reversibility is a touchstone concept for explaining modern restoration practice to the public. Ostensibly it separates old and insidious pictorial interventions from modern, sensitive, responsible and “scientific” ones. Reversibility which serves as a guarantee of safety would assure us that regardless of whatever might have transpired during the restorative process, normally including cleaning, the final appearance of a painting can always be returned to its previous state by the flick of a wet sponge. Any repainting or integration undertaken can be undone because all such applications are executed with water soluble paint. Hence in merely a moment, all the problems of questionable interventions can be safely eliminated, since, we are further assured, any overpainting, is separated from the original by a layer of varnish which serves as the base for the new painting. Thus what is left of the old and original (albeit newly cleaned) surface is effectively insulated from the modern repainting.

This rationale, incidentally, begs the question of the status of the new varnish which has been applied in preparation for the over painting, not to mention the status of the varnish which is always applied to the whole picture as a final step in any restoration. This latter varnish covers everything on a painting’s surface, including the reversible water paints. Varnishes are not water soluble, but require a chemical solvent for removal. Although such an operation may be the harmless exercise that we are told it is, it is also possible that the chemical properties of the solvents will act in unpredictable or unwanted ways. Nevertheless, this is a side issue for the purposes my present discussion.

As the official line of explanation runs, the art object is always safe from irrevocable alternations because of the reversibility of the colors applied. However, is this contention, one which is central for restoration rhetoric if not for actual practice, really true? Or can the notion of reversibility be shown to be anything but reassuring? I shall, in fact, argue that reversibility as a concept should be regarded with deep distrust.

To start, one should recall that reversibility, as an operational approach, is only applicable to the second stage of the normal restorative process: the stage following the repairs and cleaning of the surface. The actions taken during this first stage, are never reversible, since they all involve the process of (permanent) removal of certain material or substances. To be sure there are always choices as to what is to be removed and what is to be kept. That is, the restorer must correctly identify and then contend with dirt, old varnish, old repaints, etc. Following the restorers intervention, anything that has been removed, even if removed in error, cannot, of course, be put back. It would not be a mistake here to clearly and unequivocally state that we have a virtually surreal condition in which an application commonly regarded as a reversible one is superimposed upon an irreversible one.

To further compound the problem, the notion of reversibility has a subtle yet significant impact upon this first stage of cleaning and fixing. It is an effect that is never considered but one that can determine the integrity of the restoration’s final result. The recognition on the part of the restorer that from the very beginning of the intervention process she/he will be able to change the original surface of a picture once the restoration is at the second stage, including even the painting in of lost areas, modifies and can give fatal direction to every step in the restorer’s procedure. In other words, the restorer is fully aware that with the reversibility methodology in place, there is nothing which cannot be “corrected” or unified by means of subsequent in-painting, use of toned varnishes, or the adjustment of light. Consequently, the concept of reversibility affords license and wide latitude in the cleaning operation because the restorer knows full well that later in the process any unfortunate events produced during the first stage of the restoration can be remedied.

The situation can be readily followed by turning to the current, much labored and widely heralded restoration of Leonardo’s Last Supper. This work has suffered devastatingly from aging and endless interventions in the previous centuries and these effects are compounded by the presumed use by da Vinci of an experimental technique which decreased the durability of the painting. Many areas of this painting reveal only tiny islands of original pigment adrift on a pockmarked surface, a condition exaggerated by the current twenty-year campaign which has sought with authoritarian insistence to remove all of the repaints old and new, as well as to make repairs for the avowed purpose of getting at what is regarded as the original Leonardo. This radical action was permissible because the restorer from the very outset knew that she would eventually fill in or at least adjust the losses on the surface with the semi-neutral application of water based colors or with more substantial repaintings and outlining which one can readily see in the heads of certain Apostles and in the head of Christ. These are not true restorations but reconstructions. They are the restorer’s interpretations of what the originals might have looked like.

Obviously, no matter how careful and conscientious the removal of the old repaints has been, the jagged irregularity of the edges of the original bits are altered, even if only slightly. Since there is so little of Leonardo’s paint left on the surface in the first place, the realization that an opportunity will be available later to correct whatever one wishes, has given the restorer courage to remove, for eternity, more than she might have otherwise. We are here dealing with the tangible results of the superimposition of what is rightly or wrongly regarded as a reversible application upon an irreversible one: the restorer can, and here has, moved ahead without trepidation. Everything can be adjusted in the next round.

Not only does this argument apply to wall painting (including both Leonardo’s puzzling a secco technique in addition to standard buon fresco), but pertains to panel and canvas paintings as well, whether executed in oil or in tempera. In these cases, where flaking has occurred the restorer is virtually obliged to adjust the edges of the remaining areas in order to prevent further deterioration, by filling in the missing portions, large or small, and eventually by adjusting and over painting those very same areas with water soluble colors.

However, we must return to the original question: Can the integrations, in painting and repainting really ever be reversible? In those areas, for example, where a new ground has been applied and then painted over with water soluble pigments, several factors must be considered. To return to the case of the Last Supper with its small islands of Leonardo’s original pigment, the removal of the surrounding modern water color repainting could prove to be dangerous to the precarious edges of these passages. Even the slightest pressure could cause losses. Any sort of rag, cotton swab, or sponge has the potential of lifting or agitating the contours of what is left of the great master. Clearly this is not reversible.

Another inherent problem is that water colors tend to lighten over the decades, so that what might have appeared to be an efficient reintegration of a painting or fresco can, in the future, prove to be totally inadequate as the colors of the new passages lighten. At that point, a new intervention would be required. Of course, the speed of the lightening process is dependent upon how much light the object is subjected to. Hence it becomes desirable at least when considering the water color integrations, to place newly restored pictures in relative darkness or to cover them with tinted glass, as some museums have chosen to do. The sensitive viewer, as a result, is put at a irrevocable disadvantage in either case. Any gains in readability, (another slogan of modern restoration), have effectively been lost.

A practical issue which should be aired in any discussion regarding reversibility. Following a state-or-the art cleaning and integration, what situation would be left by the removal of any reversible applications? Certainly removal cannot take place until one is prepared to create a new and presumably better application, otherwise all one would see is the cleaned picture with all its bare spots, faults, and other signs of preparation. To leave a picture or fresco in such a wounded state for public viewing would be unthinkable. Ironically then, reversibility inevitably demands another reversible application.

Also from the functional point of view, a further limitation on claims of reversibility can be raised. It is difficult to imagine that anyone would be prepared to provide funding to dismantle a recent, highly acclaimed restoration (and all restorations are highly acclaimed) after the first set of elaborate restoration procedures. Each step of the cleaning, preparation and reintegration process was paid for by a convinced sponsor, often a bank, insurance company, international oil giant, clothing manufacturer, cigarette maker, governmental agency, museum or church. Once the publicity of the original intervention has served its function, the desirability, in terms of public relations, to go at an artwork for a second time is seriously inhibited. Funding would be a virtual impossibility, which means of course that practically speaking, a reversible intervention would not occur.

Finally, the issue of reversibility can be approached from an entirely different point of view, not from the physical properties of the painting or fresco, but from one that modern art criticism hold extremely dear: that of the viewer’s reception. (As an aside, it worth noting that the discourse surrounding modern restoration practice has been totally insulated from the critical process, ostensibly because of restoration’s presumed scientific and/or technical character.) The actual and current appearance of a painting or fresco following a restoration, whether or not reversible materials and techniques were used, is of course, crucial to its reception.

Appearance is rarely if ever reversible in the mind’s eye. Once a particular appearance has been created, there it is and there it will remain for generations. This is especially true of our era in which most perceptions of the art world are dominated by reproductions, compact disks, videos, color slides and computer images. After the restoration of Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love from the Borghese in Rome, or the same artist’s Venus of Urbino, in the Uffizi treated several years ago, it was the newly refurbished and interpreted images which poured into the public domain, in the form of post cards and posters and in the monographs and handbooks of art history. The old appearance of the paintings are fading into the recesses of the past. The insidiously overcleaned Sistine Chapel frescoes with their repaintings and adjustments whether reversible or not, is now the Michelangelo. To the floods of visitors in the millions, who experience first-hand the “reversible” restoration, the memory of the pre-restoration version becomes increasingly vague. The newly concocted but “reversible” appearance of Christ in Leonardo’s Last Supper has been presented to the mass media quite recently as more “original” than it appeared before. It has been very heavily re-elaborated by the modern restorer, presumably in water colors but, reversible or not, it will very quickly become the correct and only image of the Last Supper.

In the last analysis, the concept of reversibility, as I have claimed at the outset, is a kind of palliative to make the public and even the specialists accept the changes and interpretations of modern restorers. If my analysis is correct that reversibility is only an imperfect theoretical notion which does not find confirmation in actual practice, we should be even more alerted than ever to the effects of modern restoration on painting. We must come to the realization that these interventions become the works themselves. Each and every restored and reversible passage is perceived as part of the whole and therefore becomes inseparable from the whole in any reading. This understanding, in turn, should encourage a highly cautious and even skeptical view of the restoration of paintings. There are undoubtedly instances when thorough restoration is necessary and even desirable, as when pictures have suffered from floods or other natural disasters, not to speak of vandalism and war nor of the more mundane but equally threatening effects of simple humidity or inattention. However, in the normal course of things, any restoration undertaken, no matter what the circumstances, as a proposal or an experiment to return an object back to its original state, must be regarded with extreme skepticism.