The Conservation Laundering of Illicit Antiquities

Einav Zamir

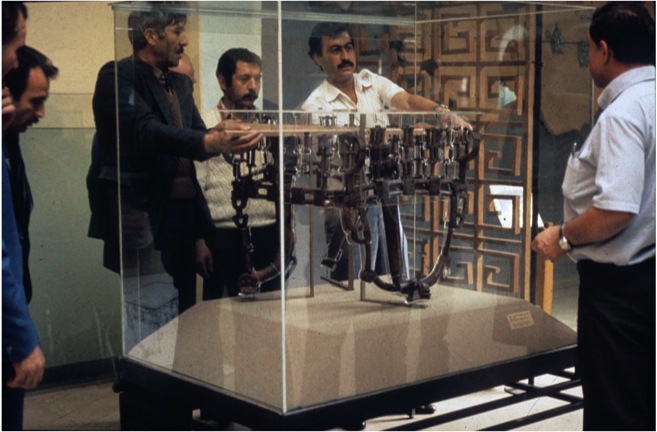

Marion True, former curator of antiquities at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles [Fig. 2], once hailed as the “heroic warrior against plunder,” [1] was indicted in 2005 for violations against Italy’s cultural patrimony laws.[2]

Marion True, former curator of antiquities at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles [Fig. 2], once hailed as the “heroic warrior against plunder,” [1] was indicted in 2005 for violations against Italy’s cultural patrimony laws.[2]

True became the first American curator to face such charges [3] — not coincidentally, it was also the first time that a source country had the means, financially and politically, to investigate and prosecute violations of their cultural patrimony laws [4]. The Swiss police and Italian Carabinieri’s raid on Giacomo Medici’s warehouse in Geneva a decade earlier [5] exposed an elaborate system, designed to avoid suspicion from authorities [6]. The subsequent investigation threw a spotlight onto the dubious activities of museum curators.

To read more of this ArtWatch UK article, click here.