Louvre Atlanta, 2006-2009

The phenomenon of the traveling exhibition has always been a powerful tool, used by museums to boost attendance rates and bring works of art to a population that otherwise might not get the chance to see them.

But at what cost? ArtWatch has raised the issue of the danger of transporting works in the past, most recently when the Bargello Museum in Florence shipped Verrocchio’s bronze David to Atlanta’s High Museum of Art for an exhibition from November of 2003 to February of 2004, followed immediately by a two-month residency at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. Celebrated as the first time that the sculpturehad ever left its native Italy, the work, as frequently is the case, was restored for the occasion. New David, new venue, and large crowds.

The motivation is not purely altruistic, but a financial one. Attendance for special exhibitions far outpace those of the regular collections, and that increased attendance is reflected in sales. The High Museum, for example,had a record year in its gift shop the year it sponsored an exhibition of Olympic rings, and the <b>David</b> was intended to produce the same results. Hence, as the show drew near, Florentine paper products were imported to entice museum-goers. The High Museum’s new expanded site at the Woodruff Arts Center also doubled the size of the museum store and, hopefully, revenues. Also more than doubled in the last few years is their museum entrance fee, which was $6 in 2000, and is now $15.

Based on the success of previous exhibitions, the High Museum has now embarked on a more ambitious program of importing art objects, teaming up for a three-year deal with the Musée du Louvre in Paris. For a price of around $13 million (the actual sum has not been disclosed, though the compensation has been called “substantial”), the Louvre will lend to the High Museum (or, the “Louvre Atlanta”) some of its most famous artworks for a series of exhibitions. Already slated for shipment is Raphael’s portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, author of The Book of the Courtier, which will be in Atlanta for the first of nine shows, “Kings as Collectors,” from October 2006 to March 2007, at which point it will be replaced by Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego. While those works may be the superstars of the loan agreement, approximately two hundred other works will be shipped from Paris to begin their long-term stay in the new Anne Cox Chambers wing of the museum. While some of the objects chosen for travel have never left France before, also unprecedented is the length of their absence from the Louvre. It is also the first time in the Louvre’s history that they have agreed to lend not just single objects, but entire collections to another museum for an extended period. At the end of the loan, much of what had been sent to the High Museum will find its new home in the new $100 million Louvre satellite museum in the city of Lens.

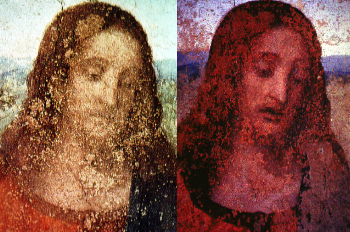

So what has led to this unprecedented situation, wherein the Louvre is literally renting out its great masterpieces? It seems as if the Louvre, while getting 60% of its operating budget from the French government, is looking for other ways to raise capital in response to recent rumblings that the museum may be receiving a cut in its federal funding. These financial concerns are surprising in light of the record attendance reported for 2005 at 7.3 million visitors, up from the previous record of 6.7 million in 2004, with the increase largely credited to the popularity of The DaVinci Code. Yet the Louvre is seeking greater autonomy from the French state, and part of the money from the “Louvre Atlanta” deal, contributed by American corporate sponsors, will be used by the Louvre to fund facility improvements, specifically the remodeling of their 18th century rooms.

As part of the partnership, the two museums will trade staff members as well, so that the Parisian institution will also get a closer look at the marketing strategies, corporate sponsorship, and fundraising techniques that American museums have been employing for quite some time. And undoubtedly they can learn a lot from the High, who had such tremendous success in their capital campaign that their chief fundraiser was jokingly nicknamed the “pickpocket.”

Despite the geo-political veil that has been cast onto the agreement — showing the collaboration of two countries that have had considerable tension over the past few years — many have been critical of the program, viewing it as a prestigious museum renting its objects out to the highest bidder. As can be expected, much of the criticism has come from within France, with the argument that the French people, rather than the museum itself, own the works and that they should not be made inaccessible to the people of that nation for the financial benefit of the Louvre. There is also some resentment that smaller French museums have had a difficult time procuring loans from the Louvre in the past, yet their shipment to Atlanta can be accommodated for the right price.

A French editorial in La Tribune de l’Art asked if American museums were more “transparent” than those in France, after noting that even after American online sources broke the story of the “Louvre Atlanta” deal, the Louvre was less than forthcoming about the objects that were to be sent abroad. To wit, criticisms have been made of the museum’s “culture of secrecy” that are, in reality, not dissimilar to those complaints made of American institutions for their unwillingness to openly share information about their collections and operations.

The aura of international diplomacy aside, big business is a much larger player in the newly brokered deal. In order to raise the $13 million to facilitate the agreement, private donors as well as corporate sponsors had to be tapped. In addition, once the Louvre deal began to arise, the costs of the High Museum’s remodeling increased as well, as amenities were added to accommodate the expected crowds, bumping the overall project budget to $163.9 million, with other reports hovering at $178.4.

While some of that money came from private donors, Delta Airlines came aboard as the lead corporate sponsor of the venture, despite having filed Chapter 11 last September and suffering a net loss of $1.2 billion in the last quarter of 2005. Delta will provide air travel and cargo shipping for the exhibition. Other corporate sponsors for the venture include Coca-Cola, Turner Broadcasting, and UPS.

The Louvre’s unprecedented action — renting out a portion of its collection for an extended period of time — has upped the level of concern regarding the loaning of artworks. Not only do the objects continue to be subjected to the substantial dangers of transport, but museums have continued their descent into corporatocracy, with no end in sight.

Featuring the 60-foot high likenesses of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, the monument was carved between 1927 and 1941 by sculptor Gutzon Borglum and team of 400 men from twenty-one granite blocks, containing many pre-existing cracks.

Featuring the 60-foot high likenesses of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, the monument was carved between 1927 and 1941 by sculptor Gutzon Borglum and team of 400 men from twenty-one granite blocks, containing many pre-existing cracks.