On Traveling Exhibitions

The business of exhibitions puts masterpieces at risk.

In recent months a controversy has re-erupted in the press and among art experts in Italy which is gradually spilling onto the international scene. Its impact upon the habits of displaying art treasures cannot be underestimated. The influential, skillful and politically adept Soprintendente of Fine Arts of Florence, Dr. Antonio Paolucci, the man who recently supervised the widely acclaimed restorations in Assisi after an earthquake rocked the basilica there, has been organizing a mammoth exhibition of Italian Renaissance art to be sent from Italy to Japan. Others shows of a similar nature have quietly been sent to Asia over the past few years, without much outcry. This one is far more encompassing in terms of the fame of the objects as well as their sheer number, in the hundreds, which will be wrapped, crated and shipped in temperature-controlled containers. Paolucci, whose impeccable curriculum vitae includes a stint as Italy’s Minister of Culture in a previous government, has been publicly attacked for his plan.

Serious objections have been raised about the dangers of shipping rare art works – Titians, Leonardos, and Michelangelos – even from Paolucci’s own usually solid ranks (e.g., the Soprintendente of the Veneto, Filippa Aliberti Gaudioso), as well as from art historians, including Professors Carlo Bertelli (who was formerly a soprintendente) and Alessandro Parronchi, the dean of Italian scholars, not to mention restoration specialist Professor Francesco Guerrieri of the University of Florence. The attacks this time have not come from art rights groups who have long ago pointed out the dangers, quite specifically when the Barnes Collection was sent around the world, but the art establishment itself, including the respected editor of London’s Burlington Magazine, Dr. Caroline Elam. Has there been a sea of change?

Blockbuster exhibitions have been a cornerstone of museum operations, at least for the past generation, being regarded as central postate in annual programming almost everywhere. These art spectaculars, looked upon with relish by the institutions’ fundraisers, the curators who participate in the planning and the structuring of the shows, the art restorers who get the objects in shape for display, not to mention socialites and firstnighters, publishers, and the press, have never before faced such a serious challenge to their legitimacy.

Positive aspects of blockbusters, and there are some, can be readily enumerated. Increased revenue which normally is expected to result from a successful blockbuster is nothing to sneeze at, planting the possibility in the minds of the cynically inclined that such is the main motivation. To be precise, increased entrance fees are not the only source of the infusion of money from the big shows. Catalogue sales, which can run into the tens of thousands of copies and even more when external sales are calculated, can produce decent revenue. Specialized products sold in the ubiquitous museum shops constitute yet another element that benefits from blockbusters, bringing the balance sheet further into the black. As a spin-off as well, the museum bars and restaurants are busier than usual when the postate are open. And, one should not forget that with the expanded attendance annual membership figures climb, and, after all, every little bit helps.

The tourism, and with it the political quotient, obviously comes into play, which is specifically the case with Paolucci’s Japanese show, an event that could not be contemplated without governmental support. The explicit intention is to demonstrate the grandeur of the Italian tradition by placing on the circuit Michelangelos, Raphaels, Titians, and Donatellos, among others. Presumably the display would add stimulus for increased tourism in Italy, just as Sensation has done so for Brooklyn, if not for all of New York. From it, we can anticipate that the waiting time in front of Florence’s Uffizi Gallery and Michelangelo’s David at the Academia will lengthen beyond the current two or three hours. Peddlers may very well benefit too by selling more postcards and knickknacks to the well-disciplined but bored tourists waiting their turn for enlightenment. The major cities with great collections, like New York, Washington, London, Paris, Madrid and St. Petersburg, have very deep ties with museums, arguably the principal tourist attraction in these cities, and all that they signify for the hotels, restaurants and shops. Art is big business and a gigantic attraction. If the blockbuster is sensational enough, everyone seems to benefit, that is, except the art works.

Less direct but equally sought after benefits of blockbusters include the publicity which inevitably can be counted on from the media. Is there a journalist who does not love an exhibition of the Young Picasso, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, or Ingres Portraits, Egyptian Gold, a Real or Fake Michelangelo Cupid, or Hans Holbein’s Ambassadors? These postate are even advertised in the mass media and in the metro to get the highest attendance possible. Together with more money and increased attendance, good will is banked for the future at the Metropolitan, London’s and Washington’s National Galleries. An analogy made be drawn with fundraising for public television which must be regarded as self-advertising that is transmitted with frustrating frequency. Over the past few years, the corporate sponsors are being rewarded with mini-ads for their largess. Are similar compromises also necessary in the function of museums?

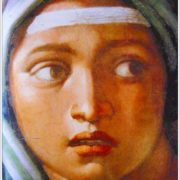

Raphael, Madonna of the Chair with St. John the Baptiste as Child, c. 1514. Courtesy: Palatine Gallery.

Together with the public relations value and the effects of expanded tourism, museum rhetoric is quick to proclaim the value of spectacular shows upon scholarship, which is regarded as a sacred cow. Scholars and specialists are able to see, compare and contrast to their hearts content, works by a given artist, school or region all at the same time. They do not have to go to dozens of far-flung museums, remote churches, obscure private collections, and dingy drawing cabinets. They can see all the objects together. To confront versions and contemporary works in a single space seems to be a unique and incomparable opportunity, and can result, the line continues, in scholarly insights and discoveries. Many, and in some cases most, of the objects of a given category or by a selected artist can be seen, one by one, until the eyes get bleary.

I cannot resist commenting that for me seeing two hundred Cezannes, or two hundred works by anybody else, makes my head spin, and in the end I get very little out of the experience except a slight case of nausea. These monstrous piling-ups are effectively less informative than a carefully and thoughtfully selected, much smaller exhibition in which a curator uses his critical skills and makes judgments based upon a studied but personal view of a given artist or school. Some sort of informed selection has been offered by the specialist, and not left to an uninformed helter-skelter viewing. In this instance, there seems no doubt that more is less, anyway. Of course a disciplined viewer might decide to go to the blockbuster eight or ten times, and look at a small number of objects each visit, but perhaps that is asking too much. Ironically, the way in which the blockbusters present an artist’s oeuvre was never even available to the creating artists themselves, for works disappeared from the studio through sales and commissions.

And there is a practical spin-off of the transport of artworks as well. The museum staffs get numerous free trips to the great cities of the world, for the purpose of scouting around during the early stages of the process while in the later one, they supervise and often accompany the travel of the art objects from their institutions. And one could hardly expect them to travel economy or to stay in second-class hotels.

Specialized studies, inevitably accompanied by weighty and usually unreadable catalogues, are claimed to be, and with a certain justification, the most prestigious art scholarship of the moment. This scholarly component, sub-vented by willing sponsors – international oil companies, cigarette manufacturers, local and national banks – gives increased legitimacy to the blockbuster and make wonderful gifts to their clients.

What is not taken properly into account is that very soon if not already with a modicum of effort, technology will be available to create high quality, exact-scale facsimiles. By substituting such computer-generated images, the questioning of the viability of shipping precious art works around the world indiscriminately will be mooted. If my assessment is correct, we may finally be witnessing the beginning of the end for blockbusters as we have known them, and the concomitant risks to the art objects will be radically reduced.

Another incontrovertible benefit will accrue. No longer will the normal permanent exhibits of museums be disrupted by the removal of ‘stars’ from their collections. Nor will the famous works be pulled out of churches and museums. After all, who wants to go to Rome’s Borghese and not see Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love (despite its recent harsh overcleaning) or Milan’s Brera and not see Mantegna’s Dead Christ? Leave the objects in their original homes or in their acquired ones, should be the rule.

A further advantage of using facsimiles, which need not be glossy, is that they can, ironically, be more accurate than the originals as they have come down to us. We know paintings have been cut down over the centuries, they have been damaged by natural disasters, and they have been severely modified by repainting and overcleanings. Reconstructions can be offered in exhibitions which aim to give the appearance of the original, and even several alternative interpretations can be presented at the same time. Furthermore, facsimile images can be updated and corrected by the computers that generate them in the first place as our knowledge expands. Of course the specialist will always need to view the objects in their current state, but that eventuality involves merely moving a few people, without threat to the safety of the art.

The facsimile alternative should turn out to be a bonanza in terms the usual goal of blockbusters for completeness. There are always works which, for one reason or another, cannot be shipped, including frescoes (except when detached), paintings and sculptures in collections with rules against loans, not to mention bulky monuments. These can all be supplied with relative ease, low cost, and considerable accuracy. The goal of what might be termed completeness is something of a pipe dream, anyway. To have all the works of a Matisse, even from a limited period, is an impossibility, if one takes into account the works that an artist himself may have destroyed, and those that have been lost or have otherwise disappeared. All the more difficult is the re-creation of total oeuvres of artists from the more distant past.

The claim on the part of museum executives is that expanded public attendance, which is a sought-after goal of blockbusters, is automatically desirable. The argument is double-edged, however, for more may not really be the merrier. That the Sistine Chapel, following its widely publicized restoration, draws double the number of persons it did before 1980 does not make visiting the chapel a sensitive aesthetic experience. The spectacle atmosphere, as with blockbusters, means that the viewer sees the back of heads instead of the Old Testament scenes and Michelangelo’s heroic Prophets and Sibyls, in an atmosphere where the noise level is crushing.

Yet ‘the more the better’ is a fixation among museum directors. Pile them in, get the mass public in the vicinity of an art work, and by an alchemical process they will be informed and enriched. Oddly enough, we do not use this argument for a concert of a Bach cantata, which needs musical sophistication and a certain amount of musical education. By merely attending a prestigious exhibition, does the uninformed viewer really benefit? Perhaps a few might be motivated to see more, but this could be more effectively accomplished by other means. After all, the permanent collections of the Louvre, the Met, the National Gallery, and the Prado are so impressive that there is no need to import other objects to get people inclined toward the appreciation of art.

Finally, the obvious danger to the objects from travel and changing environments is spoken of openly. Even if the transport and packaging skills are improving, there is no doubt that works get shaken up when in transport just as we human beings do, on those bumpy roads to and from the airport, and even by jolting movements in the plane. Beyond that, the ever-present possibility of a mistake or an accident cannot be denied, planes crash and ships still sink.

On a less material level, further questions surrounding the blockbuster can be raised. Is the circus atmosphere and the Disneyland overtones which surround them desirable? Is art served by being made into a spectacle? These issues open vast areas for cultural discourse concerning the treatment of art in a modern society which are best left for independent consideration on their own. Suffice to say that for many, art is the repository of spiritual and ethical values. It requires a commensurate treatment.