The Battle to Remember Palmyra: Daniel Johnson Speaks Out For the Artistic Heritage Lost in Its Destruction.

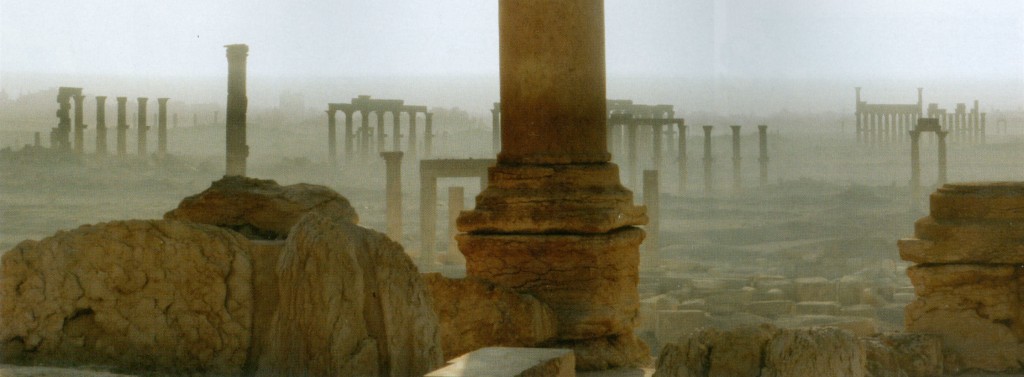

1st century city of Palmyra in Syria.

Courtesy: Standpoint/The University of Heidelberg (CC-BY-SA-3.0). © ZELEDI/GNU 1.2

Ruth Osborne

Earlier this month, news of the destruction of the ancient Temple of Bel at Palmyra by ISIS militants was confirmed.

Satellite imagery showed the area had been laid completely to rubble, only a few months after satellite footage recorded the Temple of Baal Shamin as the first architectural casualty under ISIS at Palmyra. These temples have been joined also by, according to more satellite imagery, six tower tombs at Palmyra. Before these ravages took place, an even more disturbing one occurred – the beheading of the chief of antiquities at Palmyra, Khaled al-As’ad, who spent the last forty years of his life working to preserve and protect the city’s remains. Despite videos of questionable veracity that emerged earlier this year showing the supposed smashing of antiquities at the Mosul Museum (largely plaster cast fakes) and the ancient city of Nimrud (not confirmed), the 1st century city of Palmyra is indeed at great risk to complete decimation. But why should the destruction of ancient ruins matter, beyond a shocking news story? Why should those opposed to ISIS make an effort to protect these works?

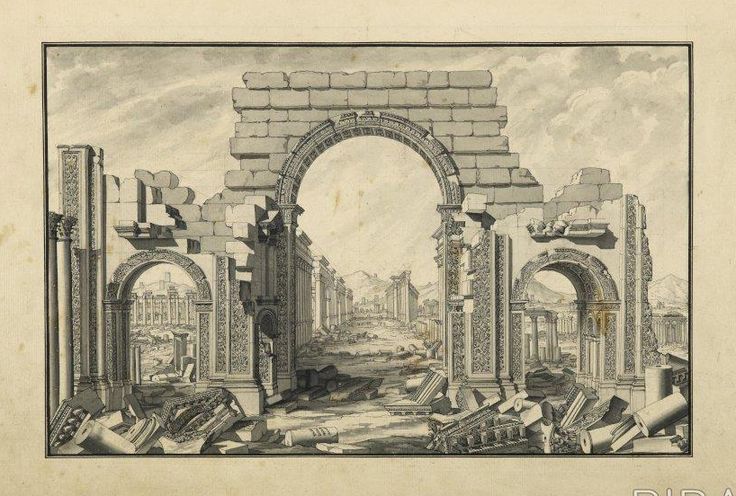

One of Giovanni Battista Borra’s drawings from Robert Wood’s 1753 “The Ruins of Palmyra”. Courtesy: The Royal Collection Trust, UK.

This question is just what Standpoint editor Daniel Johnson finally answers in his recent piece “Why Palmyra Should Matter To The West”. He points out the understandable argument against such action by political leaders – that saving lives in the struggle against ISIS militants should take precedence over saving artifacts: “To have committed even a handful of troops to save Palmyra, rather than to rescue refugees, might have implied that buildings mattered more than people. No politician dares risk a charge of lacking compassion. Hence one of the greatest surviving relics of antiquity has been sacrificed without a fight.” But he also demands the reader understand just why Palmyra should not be dismissed as a casualty in the current crossfire.

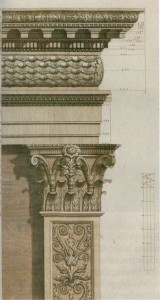

Courtesy: The Royal Collection Trust, UK.

The 1753 study The Ruins of Palmyra, which featured 57 impressively technical architectural renderings of the site by Giovanni Battista Borra, set a precedent for Western art and culture that has been far too overlooked. Borra’s attention to archeological accuracy served to depict the ruins in a way that conveyed their features for future artists beyond the romantic veil of the picturesque so admired by contemporaries like Piranesi. Influential eighteenth-century architects, from Robert Adam in England, to Thomas Jefferson in the U.S., were inspired by Borra’s depictions of Palmyra for their own respective work. Johnson argues “the debt is so extensive that a major Anglo-American exhibition is overdue. It is time that the great museums and libraries of London, New York and Washington joined forces to highlight what has been lost in the destruction of Palmyra.”

If this is so, then cultural patrimony is the driving force that has the power to draw out architectural historians and archeologists to do something about Palmyra. While such expertise may not aid in rescue missions for human lives in this crisis, it could very well serve essential in rescuing ancient cultural heritage from further destruction. In fact, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in conjunction with the U.S. State Department, are hosting a panel next week (Sept. 29) entitled “Conflict Antiquities: Forging a Public/Private Response to Save the Endangered Patrimony of Iraq and Syria”. We hope to report back on this panel, and recommend you take a look at Johnson’s informative article.

Courtesy: The Royal Collection Trust, UK.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!