A Powerful Advocate for Art: Celebrating the Life’s Work of Alexander Eliot.

Ruth Osborne

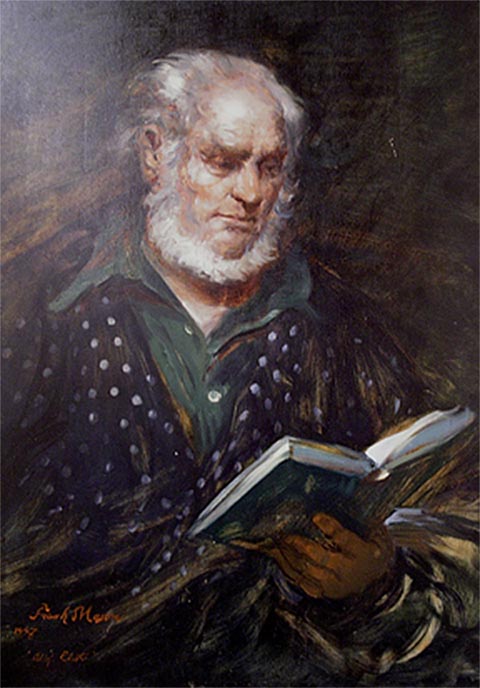

Frank Herbert Mason, Alexander Eliot (1997). Courtesy: The Salmagundi Club.

This week we are saddened to announce the recent passing of writer and painter Alexander Eliot, whose effort in the battle against the controversial Sistine ceiling cleaning had a major impact on the founding of ArtWatch and our continuing efforts to provide a voice for artistic heritage where it is all too often overshadowed by greed and prideful motivations.

Former Director of ArtWatch International, Einav Zamir, was able to interview Mr. Eliot just two years ago on his experience covering the Sistine Chapel for the landmark the 1967/68 documentary “The Secret of Michelangelo, Every Man’s Dream.” This film, at the time both groundbreaking and immensely popular when it broadcast, was created thanks to a tower that moved the researchers along the entirety of the ceiling over a six-week period. Just a few decades later, another scaffold tower would set about erasing the work of Michelangelo as it moved slowly along the immense canvas of ceiling like an eraser across a chalkboard. What Eliot and his colleagues were able to capture for the public eye via film now serves as a rare testimony to the original work of the artist before it was scrubbed by cleaners in the 1980s and 1990s.

“almost everything we saw on the barrel vault came clearly from Michelangelo’s own inspired hand. There are passages of the finest, the most delicately incisive draughtsmanship imaginable.”

Eliot’s view of the frescos before the cleaning demonstrated they were in “fabulous condition…the painting itself was all there…extremely subtle, rich, fresh, and pure.” As one given a rare opportunity to record them up close less than two decades before the cleaning commenced, his eyes, and those of his wife Jane and others working on the documentary, served as the best proof there could be that the cleaning had white-washed Michelangelo’s a secco detailing atop the under-painting.

It was Eliot’s involvement in this documentary, and his care and concern for better stewardship of our artistic heritage, that connected him with Beck at the beginnings of ArtWatch. Eliot’s efforts with great New York classical painter Frank Mason, and later ArtWatch, against the destructive cleaning of the Sistine ceiling by Colalucci and his chemists was something only to be taken on by those who viewed art as something above their own sense of pride and name. Instead of sacrificing what was handed down from Michelangelo over centuries, at the risk of coming up against the Vatican authorities, Eliot with Mason and Beck pursued a tireless campaign for the voice of art in the face of great opposition.

Anne Mason speaks of Eliot’s efforts with her husband:

“those years when Alex, Jane, Frank and so many others were desperately trying to prevent the destruction of the Sistine Chapel…those devastating years. That’s the only word that comes to mind — devastating.”

And yet, though their efforts did not change the unwilling minds of those involved with the cleaning, stubbornly standing behind their spun stories of a “new Michelangelo,” Anne still spoke with hope in the greater purpose behind their campaigning. She saw what this effort was evidence of – that people like Eliot were passionate enough to rally for the art itself, for something greater than themselves that need not be wiped out for the sake of a PR campaign.

Eliot wrote of the value of art that:

“…every genuine work of art exists in more than the material sense…To maim or destroy a work of art is reprehensible in the same degree that its creation was admirable. A masterpiece by Shakespeare or Beethoven or Michelangelo, say, deserves a natural life of centuries, not years, because it has so much to give. By the same token, it deserves to be kept free of alien encroachments if at all possible.”

His testimony is also recorded in the full-length biography A Light in the Dark: The Art & Life of Frank Mason (2011), which documents his efforts with Frank on the Sistine. His daughter, author Winslow Eliot, will continue to maintain the website devoted to her father’s writing.

By Ruth Osborne