Qing Fresco “Restoration” Yields Disastrous Results

Ruth Osborne

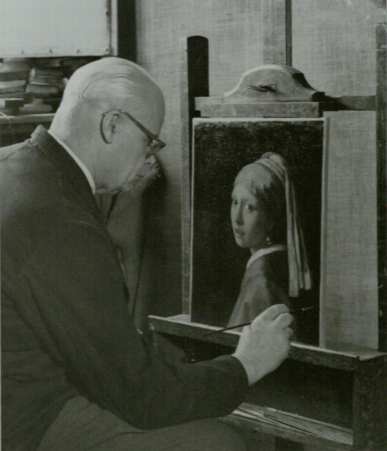

Original Qing Dynasty fresco at Yenji temple. Courtesy: AFP/ Getty Images.

Following last year’s famous botched restoration of the nineteenth-century Ecce Homo fresco by Cecilia Gimenez (Read the ArtWatch UK article here), this month brings an interesting, and equally disturbing, development in the Chinese province of Liaoning.

Earlier in October, images leaked online revealing the destructive outcome of an unauthorized “restoration” of 270 year-old frescoes from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) on the walls of the Yenji temple in Chaoyang. The new, and completely-unrelated, cartoons of Taoist mythical figures that now cover the original frescoes were carried out by a reportedly unqualified restoration company. Following the temple abbot’s denied application for restoration permits, local authorities of the Pheonix Mountain scenic area decided to go on with the project anyway.[1] According to BBC News, this indignity was uncovered by a Chinese blogger “Wujiaofeng;” Weibo users in China (similar to Twitter) responded accordingly: “Ignorance is horrible!”; “I feel some people’s brains were kicked by a donkey.”[2]

“Restored” mural at Yenji temple.

In considering these under-the-radar restoration blunders, Alasdair Palmer of The Telegraph also calls into account the irreversible harm that can come as a result of professional treatments: “if their interventions do not actually destroy far more important works of art than Martinez’s fresco, there is a growing consensus that they do not always improve them – and on occasion, they may seriously damage them.”[3] While photos of the original seventeenth-century frescoes reveal they were indeed faded and weathered by time, how is it that this condition merited a complete invasion of the temple’s visual aesthetic? The obtrusively noticeable loss of the original artist’s work at the Yenji temple sets an extreme example for just how much “restoration” can cause utterly irreversible damage.

Original 17th century Qing Dynasty fresco and its 21st century replacement.

Authorities of Henan’s Culture Relics Bureau have showed great concern for the irreversible restoration work that has forever destroyed the original frescoes, as was evinced in 1990 after the Sistine chapel cleanings (Read the ArtWatch UK article here). As with the cleaning of Michelangelo’s frescoes, the damages in China occur even under the watchful eyes of the public. Henan archeologist Li Zhanyang states: “They just use the name ‘restoration’ for a new project.” Furthermore, there are disturbing lingering reports that “restoration” damages like this occur throughout China every year. Two local officials in Chaoyang, the chief of Yenji temple affairs and the head of city’s cultural heritage monitoring team, have since been fired. For those with a keen eye for improving awareness of similar damages, the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Centre considers incidents at other historic architectural sites. The Centre’s founder, He Shuzhong, comments on issues of harmful over-restoration at the Forbidden City and Great Wall, among other sites. He relates a two-fold issue: the public desires “dazzling, new, high, big things,” while experts and officials often place efficiency over thorough research and preparation.[4]

[1] Oscar Lopez, “Chinese Temple ‘Restored’ By painting Over Ancient Qing Dyansty Fresco Wall Artwork Prompting Outrage.” 22 October 2013. Latin Times. http://www.latintimes.com/articles/9495/20131022/chinese-temple-restored-painting-over-ancient-qing.htm#.Umfn4SioflO (last visited 23 October 2013).

[2] “China sackings over ruined ancient Buddhist frescos,” 22 October 2013. BBC News. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-24625277 (last visited 23 October 2013).

[3] Alasdair Palmer, “Restoration Tragedies,” 26 August 2012. Telegraph UK. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/9498877/Restoration-tragedies.html (last visited 23 October 2013).

[4] Tania Branigan, “Chinese Temple’s Garish Restoration Prompts Outrage,” 22 October 2013. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/22/chinese-temple-restoration-qing-dynatsy-china (last visited 23 October 2013).