Has the Met Been Rewarded for Looting Antiquities?

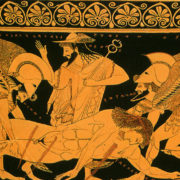

The Metropolitan Museum website may now indicate that the famous 2500-year-old Euphronios krater is “Lent by the Republic of Italy,” but that has hardly been the case since the acquisition of the object thirty years ago. Shortly after the Met acquired the krater, Italy claimed that the work had been stolen from a tomb in Cerveteri.

Despite Italian rumblings from the start, the Metropolitan, they say on the basis of switched documents, insisted that they believed the work came from a Lebanese collection. Nonetheless, proof has finally been accepted that the krater, which was purchased for $1 million during the tenure of Director Thomas Hoving in 1972 from Robert E. Hecht, was stolen from an Etruscan tomb the year before.

The Met’s deal includes the return of the krater as well as fifteen pieces of silver looted from the Sicilian site of Morgantina, acquired by the museum in 1981 and 1982. In that instance, although claims of the illegal provenance have been made since 1987, the Met has only recently acquiesced.

While many may not be surprised at the reluctance of the Metropolitan to return the objects, and the complete refusal to admit any wrongdoing in their acquisition policies, more shocking is the manner in which current and former Metropolitan officials have spoken of the matter. In a recent interview (Time Out New York, March 2006) former Director Hoving lauded Phillipe de Montebello’s arrangement with the Italian government. “It was there for 30 years. Now they can exchange it for other great things. They’re going to get fabulous stuff over an indefinite period, stuff they could never buy, never find and never afford if they found it. It’s sensational. It’s a landmark move. It’s gutsy, and I think [Met director] Philippe de Montebello did a great thing.”

Even though Hoving chalks up his acquisition of the stolen krater as the normal practice of the time, saying it occurred in the “days of raw piracy, when nobody cared,” he simultaneously touts his role in formulating the UNESCO

treaty back in 1970.

In his book, Making the Mummies Dance, the former Director wrote about the experience of landing the Euphronius krater: “I sat back at my desk shuffling black and white photos of my passion and felt a near-sexual pleasure. We had landed a work that would force the history of Greek art to be rewritten, perhaps the last monumental piece ever to come out of Italy, slipping in just underneath the crack in the door of the pending UNESCO treaty which would drastically limit the trade in antiquities. We had gained a triumphant work, one of surpassing power and infinite mystery, one, I knew, that would one day reveal surprises.”

One might, however, expect a more conciliatory attitude on the part of the current Metropolitan Director and other officials at the Museum. However, despite overwhelming evidence that the objects were improperly acquired and withheld from Italian collections for decades, Philippe de Montebello seemed less than apologetic.

The United States participated and played a key role in the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) agreement signed in Paris in 1970, entitled Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. Regardless of the government’s official position, Montebello told the New York Times shortly after the agreement was struck, “I am puzzled by the zeal with which the United States rushes to embrace foreign laws that can ultimately deprive its own citizens of important objects useful to the education and delectation of its own citizens.” His own words suggest that the only reason that the Metropolitan decided to finally address the Italian claims is because the issue, one he referred to as an irritant, did not appear to be dissipating.

Much to the chagrin of archaeologists everywhere, Montebello minimized the importance of preserving the archaeological context of objects, information that is lost when objects are stolen: “How much more would you learn from knowing which particular hole in — supposedly Cerveteri — it came out of?” he asked. “Everything is on the vase.” Despite the fact that Montebello claims that the attention given to the issue of stolen objects in recent years has greatly reduced the number of antiquities entering into American collections, the Metropolitan’s policy, dating to 2004, is not particularly rigid. It allows for the purchase of any object with documentation that dates back at least ten years, unless the object is deemed especially important.

Even with the recent decision to return several items, including the famed krater, the Met feels they have achieved something of a victory, a point not lost on Hoving. Montebello thinks the real achievement in the current agreement is not the return of stolen objects, but rather that Italy “has agreed to the principle of a fair exchange of like material.” To wit, the Euphronius krater, in deference to the re-opening of the remodeled Roman and Hellenistic galleries at the Met in Spring of 2007, will remain in New York until early 2008.

This same attitude, that no real wrong was committed, was celebrated at a panel discussion entitled “Who Owns Art” at the New School in New York on March 6th. Montebello said: “I thought that some sort of formula where reciprocity and exchange could be arranged would be successful for both sides and not deprive the American museums altogether of antiquities when the objects were returned to Italy. As you know, Italian museum storerooms are engorged with works of art. It’s not as if they needed them. This is a political statement.” He criticized the Italian government strongly for pursuing their case through the press, calling the process “shabby”. The audience, reportedly composed largely of collectors who paid $25 each to attend the event, was criticized by some as a staged publicity event. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the panel discussion was organized by the New York Times, a paper with notoriously close ties to the Met.

The Metropolitan isn’t the only institution to come under fire for their practices of acquisition, past and current. The Getty, embroiled in a scandal known as “Gettygate”, has been questioned regarding a full half of the antiquities in their large collection. Just recently, the villa (in Paros) of the Getty’s former antiquities curator, Marion True, was raided, and several undeclared antiquities were confiscated. True is, by the way, already facing trial in Italy for the looting of antiquities. This was followed shortly thereafter by the discovery of thousands of undeclared ancient objects in a cache located on the Greek island of Skhoinousa, many of which had been purchased by Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Authorities have released few immediate findings, but there was an expressed interest in determining if any of the objects were intended for the already embattled Getty Museum.

The scandals may grow tiresome, but museums, especially public institutions like the Metropolitan, have a responsibility to the public, and they should show an interest in serving more than their legacies.