Ship lost at Clark. Many records feared missing. Establishment unfazed.

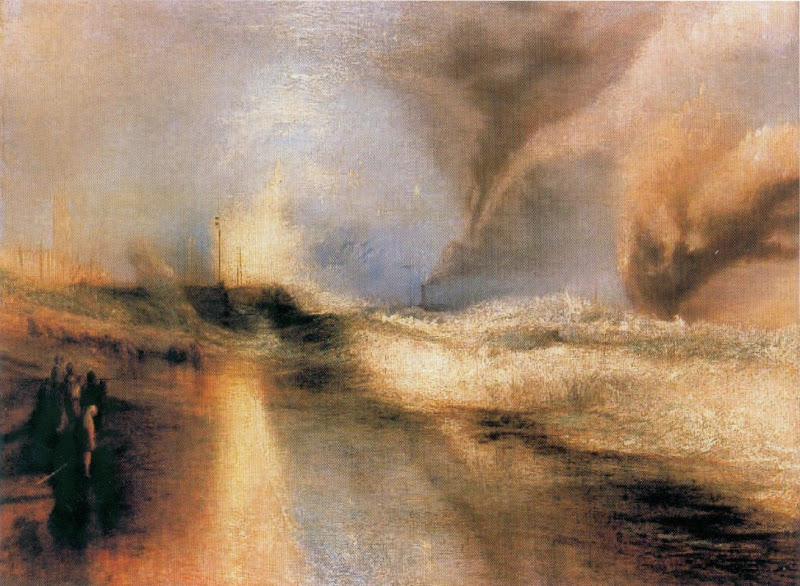

1896 photograph of Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights. Courtesy: Christie’s.

In 1932 a black and white photograph of the picture was supplied with other material to Sterling and Francine Clark by the dealers Knoedler as an inducement to buy the picture – which they did that same year. This photograph and later color photographs were shown by Mr. Bull in support of his claim that the paintwork of neither of the two steamboats and their plumes of smoke were by the hand of Turner.

It was certainly the case to my eye that, in those photographs, the plumes of smoke had a very dense and uncharacteristic look to them – resembling tornado funnel clouds and lacking the atmospheric quality evident in the rest of the painting.

While the claim that the handiwork of an earlier restorer or restorers was present was uncontroversial, Mr. Bull’s conclusion that the boat (and its plume of smoke) on the right of the picture had not just been repaired or modified but was probably entirely the product of some restorer’s imagination and therefore “ethically” removable, was anything but. In support of his startling contention, Mr. Bull projected an image of a chromolithograph copy of Rockets and Blue Lights credited to Robert Carrick. This “evidence” was utterly perplexing.

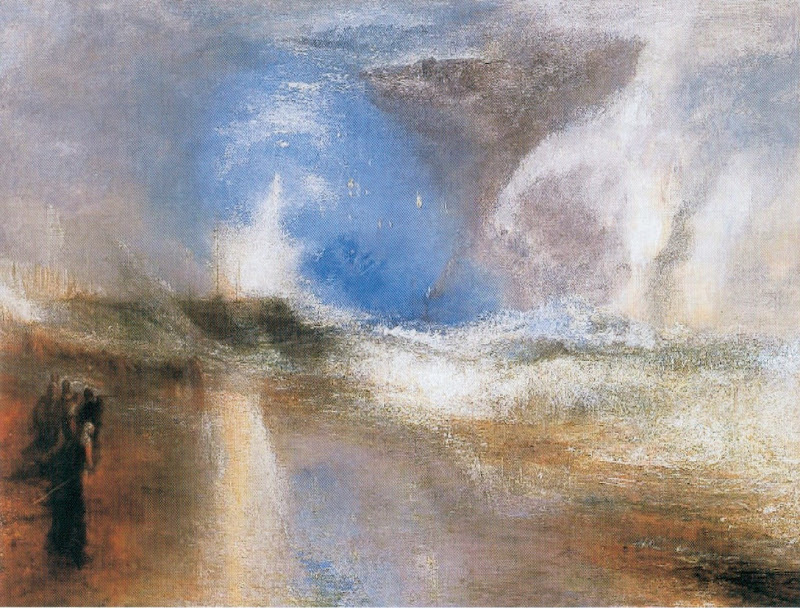

1852 lithographic copy of the painting by Robert Carrick.

As is well known in Turner literature, Carrick’s print of 1852 and a large watercolour copy of it made before 1855 by Whistler no less, both show two boats. A second (c. 1845) now missing painted copy/version of Rockets that has been drawn to our attention by Douglass Graham, director of the Turner Museum, Sarasota, Florida also shows two steamboats.

And yet, in the projected “Carrick” print shown by Mr. Bull, the colours were strikingly light and bright and there was indeed, only a single steamboat and plume of smoke – that being the more distant of the two in the picture’s centre. On the testimony of this singular version of the Carrick copy, Mr. Bull removed all surviving traces of the right-hand boat and its smoke plume along with earlier and crude retouching of them. Further, it seemed clear that in the course of his restoration, Mr. Bull had brought the tones of the painting itself into line with those of the Carrick image he had shown. But from whence had this image sprung – and what precisely was its evidential status?

During the question and answer session I asked if the lithographic print shown was the one produced by the publisher R. Day who acquired the painting in 1850 in order to publish the most accurate print reproduction of it that technology permitted. Mr. Bull and Mr. Rand looked first at each other and then down at a piece of paper on a small table between their chairs. Almost simultaneously they said that they had no idea that Mr. Day had owned the painting. Mr. Rand picked up the piece of paper, saying that it was the provenance of the Rockets and nowhere on it could he or Mr. Bull find any reference to Day’s ownership of the picture. Before I could respond to this surprising claim, another question was taken from another member of the audience. This was disconcerting.

The most widely recognised and comprehensive reference work on Turner is the Yale University Press’s “The Paintings of J. M. W. Turner” by Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll. Although the first edition of 1977 makes no reference to Day’s ownership, the revised second edition of 1984 certainly does. The entry there on Rockets acknowledges that the Turner expert Selby Whittingham had kindly drawn the authors’ attention to Webber’s book on Orrock, a one-time owner of the picture. In it, letters from Day are cited that establish not only his ownership of the picture at the time Carrick was employed to make his copy but that it had been acquired by Day for that very purpose.

Turner’s Rockets and Blue LIghts after William Suhr’s 1960s restoration.

Even if Mr. Bull and Mr. Rand had overlooked the Butlin/Joll 1984 revision, it remains bewildering that they should also seem unaware of the actual appearance of Carrick’s print, as reproduced in the many recent books on Turner and in all of which two steamboats are present. Indeed one such book, the catalogue to the 1998 “Turner and the Scientists” exhibition held at the Tate Gallery, London, was written by James Hamilton – the curator of the Clark’s own exhibition. Did Dr Hamilton express no alarm at the disappearance of one of the two boats about which he had himself commented? It must be thought odd if he had not: the Random House edition of his own 1997 monograph “Turner” has a colour plate of the Clark’s Rockets and Blue Lights, the caption of which states that the photograph was taken before Mr. Bull’s 2003 conservation treatment.

The plate of today’s post-restoration Rockets in the Clark exhibition catalogue shows a strikingly different work. This being so, must we assume that Dr Hamilton believes that some restorer had added a second boat to Turner’s picture between 1851 when Turner died and 1852 when Carrick copied it? If he does, does he have any evidence for it?

In William S. Rodner’s “J. M. W. Turner: Romantic Painter of the Industrial Revolution” (University of California Press, 1997) the author speaks of one ship and her “sister” in text pertaining to the Carrick copy (shown in his figure 33, page 77).

With regard to the evidential value of the Carrick copy, it is important that it be appreciated how unusual and painstaking a production the print was. Day & Son published a collection of plates entitled “The Blue Lights by R. Carrick, after J. M. W. Turner shewing the progress of the printing.” There were no fewer than 27 colour plates. Fourteen plates show each of the single, separate tints that went to make up the image. A further thirteen plates show the successive superimposition of the fourteen tints. Could the image taken as a point of reference by Mr. Bull and the Clark’s curators for their re-working of the painting, I wondered, have been from an earlier, incomplete stage of the printing? (It was, for sure, not the print’s final state.)

A set of the Day & Son’s plates is held by the Yale Center for British Art. Since August 4th I have tried repeatedly to make an appointment (through the Center’s curator for prints and drawings, Mr. Scott Wilcox) to examine the plates. My calls have yet to be returned.

In further justification of his own reworking of the picture, Mr. Bull suggested that the second boat might originally have been added to the picture by the dealer, Lord Duveen in some attempt to pander to the collecting tastes of wealthy Americans. (Twice as much boat for their bucks?) With this suggestion, he was patently and doubly in error. Firstly, Duveen had bought the picture in 1910, some fifty odd years after Carrick recorded two boats in his copy. Secondly, the testimony of the (real, final) Carrick print is corroborated by a black and white photograph of the painting itself published by Christie’s in their catalogue for the June 13th 1896 Sir Julian Goldsmid sale. At that date, the painting and its earlier chromolithographic copy were still quite remarkably in accord. Whatever and whenever damage was done to the Rockets, it must largely have post dated that period and it certainly never included the addition of some allegedly “fictitious” second boat. (Carrick and Day were both alive at the time of the famous Goldsmid sale. Neither is known to have complained about the Rockets’ then condition. At that date, Day, as Dr. Whittingham has reminded us, still greatly regretted having had to part with the picture.)

Image Courtesy: Clark Art Institute.

Ignoring, or ignorant of, all testimony to the second steamboat’s original presence in Turner’s picture, Mr. Bull offered the nowadays Standard Restorers’ Technical Defence in support of extensive removals of paint – namely, that the removed paint had flowed over and into pre-existing cracks in the painting and therefore must post-date Turner’s handiwork by a long interval. When, as here, claimed technical testimony is in such manifest conflict with hard historical testimony, it merits the closest scrutiny and requires some public demonstration and corroboration.

When someone asked Mr. Bull after his talk what had been done to the painting when in the hands of the restorer William Suhr during the 1960s, he quipped that he had no idea, as he was not there at the time looking over the restorer’s shoulder. The jibe cuts both ways: Mr. Bull was there during his own restoration. He claims to have maintained a meticulous daily log of his activities when restoring the picture – and that these logs were submitted on a regular basis to the Clark Institute. Do these records show how Mr. Bull established “technically” that no trace of the right-hand boat – not even the abraded mast and rigging that was still visible in the colour photograph reproduced by Butlin and Joll – was original? Given that Mr. Bull’s technical claims are greatly at variance with the historical record, who might adjudicate here?

When asked what supervision had accompanied his own restoration, Mr. Bull cited the involvement of three individuals associated with the Clark and the nearby Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art – one of the former being the Clark’s own Director, Michael Conforti.

A room at the Clark exhibition was given over to a video presentation in which Mr. Bull and Dr. Hamilton both take pleasure with Mr. Bull’s radical alteration of the picture. I called the Clark Institute to ask the videographer if at any time during the taping Dr. Hamilton had expressed any reservations about the removal of one of the boats. To the contrary, he stated, Dr. Hamilton had expressed nothing but praise for Mr. Bull’s interventions. This raises thorny questions. Was there ever any debate on the propriety of such a radical revision between the restorer, the curators and Turner scholars? If there was, did no Turner scholar caution that the final state of Carrick’s 1852 print and the 1896 Christie’s photograph both clearly show two steamboats? We must assume that none had – how else might Mr. Bull have believed the second boat to be an addition at the hands of Duveen’s restorer?

Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights after Bull’s 2003 restoration.

Postscript

In the absence of any response from the Yale Center For British Art’s Mr Wilcox, I decided to take up these matters with Gillian Forrester, an associate curator of prints and drawings at the Center. Ms. Forrester gave a talk at the Clark Institute’s Turner Lecture Series on August 23rd entitled “‘Enshrined in Mystery, and the Object of Profound Speculation’: The Double Life of J. M. W. Turner”. Ms. Forrester pronounced the Rockets restoration a “resplendent” return of original glory. At questions I asked, apropos of Mr. Bull’s restoration, if any of the Yale Center’s proof sheets of the Carrick lithograph showed only a single boat, and if so, at what point in the succession of superimposed plates the two boats appear together. Ms. Forrester expressed happiness at my question but unhappiness at her own inability to answer it. She had only been made aware of the Carrick proof plate portfolio two days earlier and had not at that point had chance to look at it. Perhaps she had become aware of it in the context of my many unsuccessful requests to examine it. At any event, she did invite me to come to Yale for just that purpose.

I later succeeded in getting a call through to Ms. Forrester in order to arrange the visit. Unfortunately, she said that because of a strike by certain Yale employees, it might not be possible to accommodate me in the near future. Months later, with the strike long since passed, and despite leaving further voicemail messages, I have heard no more from Ms. Forrester.

On October the 8th I put a call through to Mr. Bull at the National Gallery, Washington. Could he say which of the successive thirteen states of the Carrick print he had worked from? He could not. He referred my inquiry to Mr. Rand because he had not, in fact, worked from a Carrick print after all but from a photograph [!] supplied by Mr. Rand of some print about which he (Bull) knew nothing other than that it originated in the Yale Center for British Art.

On October the 9th, I left a voicemail request to Mr. Rand for an opportunity to discuss these matters. To date, he has not responded. Mr. Rand, as mentioned, is the Chief Curator at the Clark Institute. As such, he is answerable to the Director, Mr. Conforti, who in turn is answerable to the Board of Trustees. The reaction of the Clark Trustees to this debacle might well come to be taken as a litmus test of the probity and accountability of the wider system of stewardship that presently governs our public art institutions.

Edmund Rucinski, former Fulbright Scholar, art director of New York City’s department of cultural affairs, and Board Member of the National Society of Mural Painters, is a painter, musician, and an orchestral concertmaster.

The full text of this article is published in ArtWatch UK’s Winter 2003 Newsletter

To contact ArtWatch UK, e-mail artwatch.uk@gmail.com

Notes

¹ Manchester Art Gallery, November 1st, 2003 to January 25th, 2004. For information, call Kim Gowland, Manchester Art Gallery, on 0161 235 8861.

² Margaret F. MacDonald: “James McNeill Whistler, Drawings, Pastels, and Watercolours, A Catalogue Raisonné”. Published for The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by The Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1995.