Debunking the “Have You Seen It?” Myth

By James Beck

It took me too many years to arrive at a fundamental realization regarding the modern restoration industry, its various branches, subdivisions, and operatives.

It took me too many years to arrive at a fundamental realization regarding the modern restoration industry, its various branches, subdivisions, and operatives.

Underlying much of the activity is, of course, money, a factor that I had understood from the very start of my own involvement in the issues fifteen years ago. People need to pay the rent and eat, and it is readily appreciated that everyone down the line — the restorers and their underpaid assistants, their technical backup, their suppliers, the publishers who grind out the expensive new books after every important intervention, the journalists who soak up the news of restorations like a sponge, the art scholars and critics who write the texts, the booksellers and advertisers, the sponsors and their affiliates — has to eat. For better or for worse, this can be apprehended as a fact of life, although not necessarily an admirable one.

An additional element or, better stated, a probable motivation is that of fame, publicity, being invited to the right parties, being on the cutting edge, being envied, being hailed in the mass media as uncoverer, being sought after as a person deeply involved in the rediscovery of Leonardo’s original miracle, of Piero della Francesca’s real color, of Hans Holbein’s true intentions. By an alchemical transference, those involved in highly visible restorations (alas, no one cares about unimportant or minor ones) seem to accrue some of the creating artist’s force and genius. Who does not desire to appropriate even a fragment of Michelangelo’s power, Masaccio’s monumentality, Rembrandt’s insights, or Cézanne’s structuring? I have reluctantly and sadly understood that all of this is a fact of life, too. The Preacher of long ago knew very well the dangers of Vanitas.

For some time, I have also recognized that great museums of the world are deeply conscious of their reputation, together with the realization that the restoration of their objects goes a long way in defining them. Everyone (except, seemingly, the individuals directly involved) recognizes that London’s National Gallery has had — and continues to have — a dreadful record, perhaps close to the top of the list of world-class institutions that have systematically ruined masterpieces under their guardianship. The Prado, which has justifiably come under severe attack by a Spanish weekly, El Tiempo, is earning for itself a similar reputation. Washington’s National Gallery is hardly better as it advocates the English method of scraping everything off and then doing it over. And God forbid if there is “yellowed varnish” — worse, even, than yellow teeth. Nor is the Metropolitan Museum in New York immune to similar characterization. To be sure, its old-master collections have been systematically over-cleaned for generations, as its director once admitted to me, so there is not much left to argue about. The Louvre’s record is spotty, with some restrained interventions while others have been zealous. Raphael’s Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione has become a dingy but heavily varnished gray and now looks more like a Manet than it should. And so it goes. Although the pride of the museums can be understood, with long and often distinguished traditions, their actions must be evaluated critically and not praised indiscriminately merely because we “love” the Louvre, the Met, and other grand institutions. On the other hand, I can say that the State Museums in Berlin, Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, and the Hermitage have avoided the worst scenario and have every reason to brag about having practiced healthy restraint. One can only hope that the temptations of vast sums of American foundation money will not induce them to drop their time-honored methodology.

The element I had fundamentally failed to evaluate properly until now is that even governments believe that they have a vested interest in conservation and restoration activities conducted within their borders or carried out by their citizens. A misplaced jingoism prevents dispassionate and disinterested international debate. And, worse still, it silences those within a country who, if they are inclined to speak critically about a particular restoration, become fearful of injurious repercussions or fail to enunciate their reservations out of misplaced solidarity or assumed patriotism. In Italy, the government has effectively blocked criticism of the endless, questionable Last Supper cleaning and repainting. To have spoken out meant surely being blacklisted from various perks that the minister of culture and the mechanism in general can provide, and very few have taken the risk.

One of the standard techniques used to stifle criticism is the demand on the part of the restoration process that individuals inclined to express reservations must have closely inspected the cleaned and restored work before being considered credible. The Sistine Chapel restorers and their public-relations consultants were particularly skilled in refining this requirement. For example, if one actually saw the restored ceiling in person and still harbored suspicions, the question was raised about how much time was actually spent on the scaffolding. If it happened to have been a brief visit and an individual continued to be unconvinced, he would be belittled since he had been there only an hour or two. If resistance persisted, another ploy was used. The question was raised about how many times the unconverted individual actually saw the restoration in progress: if only a few, the naysayer was described as unserious or poorly prepared to comment.

And if one miraculously passed all these prerequisites and stood firm, the demands were expanded. For the really stiff-necked, the requirement became: one really should have followed the work step by step, day by day to understand fully what had been done. Of course, the only people left after all these conditions were met were the restorers themselves and a handful of supervisors connected with the cleaning and repainting. This systematic elimination of criticism turned out to be a brilliant tactic for stifling serious debate. And even if all the tests were passed with flying colors, one failed anyway, for “it is as difficult to judge a restoration as it is to judge a surgical operation” (E’ difficile come giudicare un intervento chirurgico], according to Dr. Giuseppe Basile, a top official of the Istituto Centrale di Restauro, in a talk presented to the Accademia dei Lincei. In other words, there can be no criticism; leave it to the operatives; do not rock the boat.

Argumentation along these lines has been so powerful that persons who might have an opinion about one or another restoration refrain from expressing themselves publicly on the subject. They have, in effect, been brainwashed into thinking that, after all, they cannot utter a word until having seen firsthand the finished product. Sometimes they never to because not doing so is an excellent way to avoid taking a stand on a controversial cultural issue, and I know of art historians who make it a point never to see recently restored works (and who can blame them?). Not having seen them, these scholars are effectively off the hook. I have sought for years, with no success, for a competent sculpture expert to comment on the restoration of the fragments from Jacopo della Quercia’s Fonte Gaia in Siena, which are systematically being cleaned. Either these experts have not seen the pieces or they pretend they have not seen them.

After moving around the edges, I am now prepared to deal with the issue straight on, seeking to impose a little logic on the “Have you seen it?” qualification imposed by restoration proponents. The requirement of up-close viewing is nonsense. In the first place, the presentations are often manipulated by theatrical lighting and, under any circumstances, not the lighting that the artist envisioned for his painting. Then one must suffer through the restoration rhetoric of official explanations. The purpose is to find out whether the person “likes” the result or not. Of course, liking or not liking the appearance of a recent restoration has nothing to do with its accuracy, historical correctness, the losses and gains, the changes, not to mention the quality of the intervention. Many people “like” the new Sistine Chapel frescoes as they might like a B movie or a popular musical comedy, but what does that signify about the quality of the cleaning? Liking or not liking the new appearance does not deal with the issue of authenticity or the need for restoration and has little to do with a critical evaluation of the intervention. On going to the refectory to see the restored Last Supper, one finds an isolated artifact out of contact with its history. The previous state (or states) is (are) gone forever so that serious comparisons are impossible.

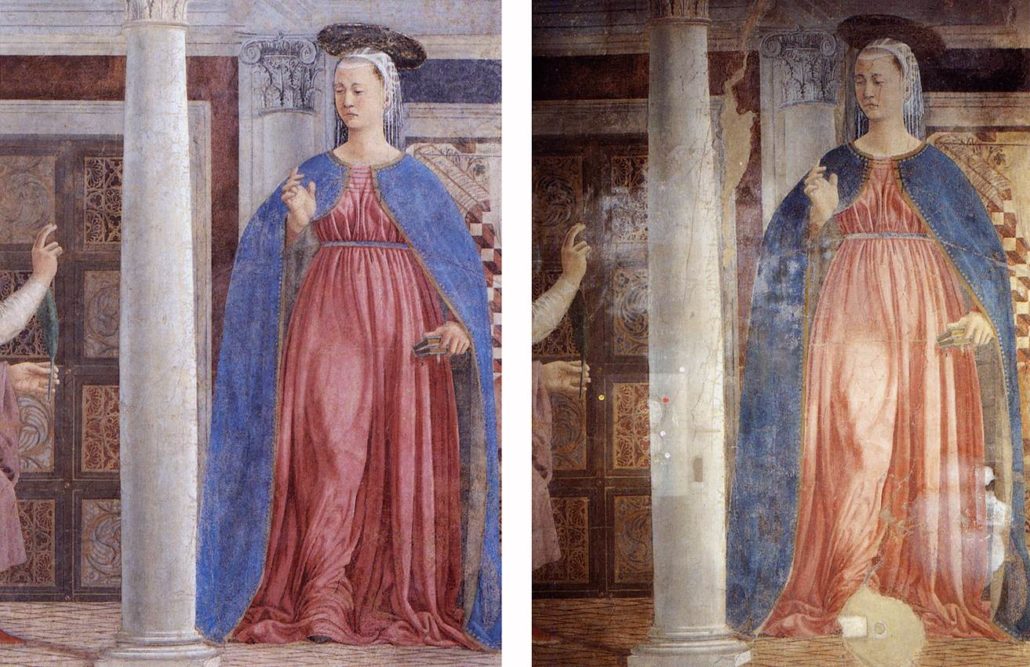

The truth is — as serious scholars have recognized for decades — that, as in advertisements for weight-loss programs, seeing is believing. Only the combination of a “before” and “after” view can produce a sensible conclusion about a restoration; even expert memory has limitations. Who can now “revive” in his mind’s eye Masaccio’s Brancacci frescoes after fifteen years and with all the verbiage that has poured forth in the interim? Careful confrontations are necessary; ones that respect scale are a requirement. In other words, holding a book of color reproductions of the pre restored object and comparing it with the original on an entirely different scale is not illuminating. A more critical study can be carried out with quality photographs, which art scholars have used to advantage as aids for more than a century. Ideally, the photos should be in black and white, for variations in color merely add a further complication to a proper confrontation. But even a one-to-one comparison is not sufficient for a balanced evaluation in this day and age. Before repainting is begun, one needs vital “during” photographs as well in order to determine what has been taken off. Further evidence can also help, including raking light, infrared reflectography, ultraviolet and X rays, which can often provide evidence upon which to base a reasoned judgment. Merely to go before The Last Supper as it now appears and to utter an impressionistic evaluation is beside the point. The requirement should be not “Have you seen it?” but “Have you studied the evidence in a dispassionate, independent way, using the whole range of unavailable evidence, including ‘before,’ ‘during,’ and ‘after’ photographs?”

Seeing the restored original has a built-in disadvantage for evenhanded critical evaluation. The aura of a Leonardo or a Correggio, however much it has been belittled by restorers past and present, retains enough of the creating artist’s ingenuity to overwhelm. The restoration establishment and their sponsors collect the benefit of whatever is left of the original to help them carry the day, even if a great deal of the original has been lost or a great deal of new painting has been added. The same is true for the Sistine Ceiling, for whatever the losses (and in my view they are considerable): all the secco, the added layers or veils, the pentimenti. But behind it all is Michelangelo, and even a fragmented, crippled Michelangelo has residual power.